Katniss Everdeen, Utopia, and The Future of Work

What is the future of work in a world of social and environmental limits? Drawing lessons from utopian fiction, and introducing the latest CUSP working paper, Simon Mair wonders if we can avoid ending up in the Hunger Games.

“What do they do all day, these people in the Capitol, besides decorating their bodies[?]”

When Katniss Everdeen, the heroine of The Hunger Games, first arrives at the Capitol, she is appalled by the fact that no-one works. Katniss grew up spending hours hunting for food, surrounded by people working all hours but living in poverty. In the Capitol, surrounded by luxury and people who do nothing all day but watch TV and play at fashion, Katniss is disgusted. This is partly because the utopianism of the Capitol rests on the exploitation of her own people. But there is also another underlying belief about the worthlessness of a workless life.

Katniss might seem a long way from economics and the real world, but she actually offers us a useful way to think about the future of work. Artificial intelligence and other technological advances promise to redefine work. And planetary boundaries and social limits mean that we can no longer rely on economic growth to provide jobs as it has in the recent past. In this context, it looks increasingly plausible that the future will consist of tech billionaires living the high-life in the Capitol while the rest of us scrabble around with Katniss in District 13.

So what can we learn from Katniss and The Hunger Games? Quite a lot, particularly when we place them in their wider context: Katniss and the Capitol are just the most recent entry into a much older debate over the role of work in the good life. In our new working paper, we trace the history of ideas around work and the good life in utopian fiction. One of the things we pick up in this exploration is that the Capitol of The Hunger Games is a form of ‘Cokaygne’ and part of a utopian vision stretching back to Ancient Greece.

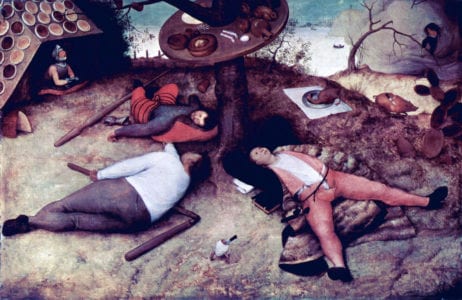

Cokaygne: a land where no-one works, and everyone feasts everyday.

Cokaygne is the name for a land where nobody ever works, yet people feast and consume as much as they like. In the Capitol this means pushing a button to reveal a feast prepared by hidden slaves, but older Cokaygnes started out without the hidden exploitation. Cokaygne has its roots in satirical takes on paradise myths, and appeals to the supernatural to separate work and consumption. In Medieval Europe, for example, Cokaygne has rivers of wine while the Judaeo-Christian heaven was often tee-total. More recently, the US-American folk song (which you should watch here) The Big Rock Candy Mountains, forbids work. But this is ok because there is no need to work. Hungry and Thirsty? Just help yourself to a drink from the gin lake, or the lemonade springs, take a freshly laid soft-boiled egg, and then finish it all off with a cigarette from a cigarette tree. No need for distillers, chefs or tobacconists here!

Opinions are split on how we should interpret Cokaygne. Some people, like Katniss, see an empty and meaningless world. In this view, Cokaygne is not a utopia but a moral lesson warning us of the shallowness of materialism and a world without work. But others see a utopian world built on a radical social critique. From this perspective, Cokaygne is actually the ultimate land of redistribution. By separating work and consumption, we are freed from market and other compulsions to work, so we can live freely. English Marxist historian A.L. Morton went so far as to argue that The Land of Cokaygne – an Irish poem written sometime around 1300 – anticipated “some of the most fundamental conceptions of modern socialism”.

News From Nowhere: a romantic, socialist utopia built on good work.

On the other hand, many explicitly socialist utopias have taken a very different view on work. William Morris, the prominent 19th Century socialist and a key figure in the British arts and crafts movement, would almost certainly have agreed with Katniss in seeing something good in work and something lacking in utopias like the Capitol.

In his own utopia, News from Nowhere, Morris describes a society in which work is the principle route to the good life. Work in News from Nowhere is a creative impulse, something people do for pleasure, for the enjoyment of the process and of contributing to society. But Morris didn’t think that this kind of work was compatible with certain fundamental features of capitalism, and in News from Nowhere he completely reshapes the economy in order to make work good.

In particular, Morris believed that the reach of markets transformed work from something good into something bad. Morris argued that the expansion of markets led to production being profit focussed, which changed the focus of production away from craft or quality towards mass production. Through Hammond, a character in New from Nowhere, Morris describes the effects of this:

To this ‘cheapening of production,’ as it was called, everything was sacrificed: the happiness of the workman at his work, nay, his most elementary comfort and bare health, his food, his clothes, his dwelling, his leisure, his amusement, his education… The whole community, in fact, was cast into the jaws of this ravening monster, ‘the cheap production’ forced on it by the World-Market.”

One of the principal ways Morris felt that the world-market and the cheapening of production reduced pleasure in work was through increasing the division of labour. In a global market, Morris argued, labour would be looked on as an economic factor of production.

What this means is that under a global market led economy, Morris believed that workers would be made to work as hard as possible and to produce as much as possible. Since Adam Smith, economists have understood that labour productivity can be improved by increasing the division of labour. In practice, what this means is splitting jobs into their simplest most repetitive tasks so that they can be performed swiftly and without creative input from workers (as this introduces mistakes), something that Morris felt was a major factor in the degradation of working conditions.

The final insult for Morris, was that under a market system “wares were made to sell and not to use”. So, workers had their work simplified and made dull and worked many hours for little pay, all to produce a “mountain of rubbish…things which everybody knows are of no use”.

To make work good in News from Nowhere, Morris does away with markets altogether. In doing so he all puts a hard limit on the division of labour, and drastically cuts down on the amount of ‘rubbish’ produced. This is his attempt to create the economic conditions under which work could be motivated by art and social usefulness rather than profit.

Towards a political economy of work for the 21st century.

What are the lessons from all of this? Katniss’s reaction to The Capitol and the role that Morris gives work in News from Nowhere chime with the intuitive understanding most of us have: that on some level, work can be both personally and socially rewarding. But what Morris also makes clear, and what we see in the utopian reading of Cokaygne is that this is dependent on the economic conditions that surround work. Cokaygne is a response to the deep inequalities that can result from making work a pre-condition for consumption. Similarly, Morris highlights the ways that dynamics that are central to growth-based capitalism (market expansion and the division of labour) erode good working conditions. Moreover, Morris offers the seed of a new kind of economy: perhaps by rolling back markets we can limit the division of labour and make work more creative and rewarding but less productive. This way we can produce less stuff and yet still maintain high levels of employment.

These lessons are incomplete, but they are important. Cokaygne solves the problem of work by ignoring the laws of thermodynamics and Morris ducks the issue of how we co-ordinate supply and demand without markets. If we want to avoid a Hunger Games style future we our task is to confront the shortcomings while heeding the lessons of News from Nowhere and Cokaygne.

Of course, this is easier said than done, can only come through a much bigger discussion. So, in the comments below, why not share your ideas for how we can avoid a future where some people live in Cokaygnian utopias while the rest of us scratch around in the dirt!

Link

- Mair, S, Druckman, A and T Jackson 2018: The Future Of Work — Lessons from the History of Utopian Thought. CUSP Working Paper No 13. Guildford: University of Surrey. Read full paper.