A fairly short, potentially useful, and reflective piece on collecting data for our qualitative research: Lockdown Version

by JOANNA KITCHEN

Why am I writing this?

In a different time, I’d be saying that the idea to write this came after a pub session; though consequences of London lockdown means that it came about after a Zoom® coffee session with some colleagues raising issues regarding disruptions in data collection for our research projects.

While practicing social distancing and the imposed isolation brought about by the COVID-19’s unanticipated extended stay, working on our research projects (or for some, starting on research projects) is probably not the highest on people’s priority lists right now. As Phil James would say, our research work is like our anchor, privileging us with some sense of purpose or agenda in such unprecedented times. I suppose we are fortunate enough to find some sort of normalcy in the work we are doing, as academics or as researchers: some even finding themselves more productive in these times. Of course, not discounting the fact that the current “normal” is not so conducive to everyone’s work continuity—though, this is perhaps a topic for another piece.

Writing this is partly inspired by David Silverman’s “A very short. fairly interesting and reasonably cheap book about Qualitative Research”, as you might recognise from my title. So, I thought I’d make an attempt to write something accessible, light and potentially relatable for some colleagues doing this kind of research. And perhaps even convince fellow data scientists to dip their toes in and test the waters.

I tend to wear a few hats: As a doctoral researcher having been involved in various research projects, experimenting with different methods of collecting qualitative data (along with my colleagues from CEEDR and CUSP); as an accounting lecturer inspired by colleagues’ (Amanda White and Victoria Clout, looking at you ladies) enthusiasm to play with technology in taking our lecture rooms online; and as a sustainability metrics consultant just trying to continue to working in present circumstance. With these hats, preference is usually being away from my laptop and just be around other humans—whether they be colleagues, research participants, students or clients.

A lot of academics, at least in the accounting and finance departments, are relatively used to working in isolation: with reliance on existing and obtainable data, or some perhaps creating novel models in the comfort of their ergonomic (home) office seats. There are, however, a fair few of us that do enjoy going out to the field; i.e. the real, messy world. The method, is arguably not quite mainstream—but that is another topic for yet a different post. But now, we can’t really go out into the real world. My main research work involves seeking various organisational stakeholders’ perspectives on social impact metrics: how they are used and observe this calculative practice in the settings in which they exist. Prior to the implementation of social distancing measures, remote interviewing and/or observation was the only option available to get in touch with some of my research participants—some due to geographical proximity, time/scheduling constraints, or participant’s preference. With the current situation, I thought my experience with these data collection detours may provide some useful insight for the current times.

Transitioning to online/remote data collection, while a fifth of the planet’s population is on lockdown, may seem daunting task, or even hopeless for some. Though these interesting, and granted—very challenging, times bring about opportunities for us to explore different ways to do our research. I can also imagine that, post-COVID19 will be forging a new normalcy of how we go about with our work and expectations of what we can produce.

Who might you be?

Perhaps, a CUSP member or fellow—like me, finding ways to continue working. Or probably a mate on one of my social media. Or perhaps a reader of a random forwarded link.

For the most part, I am writing this to share my reflections and to re-think how to go about some of our current projects. In some cases, we may have to consider other methods, other data sources or re-framing our research questions. Regardless, the current times add an interesting variable bound to shift perspectives, understandings and change the stories we are to catch. What I am saying is, all our previous work is not lost—in fact, they probably have become even more interesting. #Silverlining.

Before I get into the more technical matters of doing data collection, I’d like to share some potentially useful non-technical considerations. In this transition to collecting information via Internet technologies- we may find ourselves straddling between multiple identities. For example, most of us generally have different social media accounts: have a look at your Twitter profile, then your Facebook, compared to LinkedIn, Reddit, Instagram—and: if you are one of the millions of the recently joined, your Tiktok account. Our multiple identities then become obvious. Of course, having various representations of ourselves is not new and has performative effects. It is worth taking into consideration that the subjects of our study; as well as, us as researchers, we may be playing on a different identities compared to the kind of work we have done/were planning to do within physical proximity. The medium which we are using to conduct our data collection may likely impact how we come across as researchers/interviewers and our participant(s)’ projected might likely be different if we were to run face to face meetings, as you originally might have intended. The depth of information we are trying to obtain for our research work, or the sensitivity of the issues we are trying to explore, would likely require differing levels of trust between us and our participants. Some of this can be addressed by the medium we use and the way we conduct our interviews/meetings, but it is arguable that trust in most cases is more challenging to build remotely. Anecdotal evidence from my experience, however, I have observed what seemed like greater depth in story sharing, having interviewed remotely. Interviewees seemed more “open” particularly when discussing quite sensitive topics. I should point out, that the interviewee opted for a video interview in their own space, while the alternative at the time was to hold the interview in their organisation’s main office in a glass walled room. Moreover, the interviews were only audio recorded while assuring their anonymity.

Some sociologists may even argue that we may be “less real” behind a screen or on the other end of a phone line. In fact, some have argued that running interviews or focus groups take the participants away from their “natural settings”; again: not really a debate I would get into right now.

Remote data collection (online or on the phone), in itself, is quite a flavourful ingredient added into our research methods mix. Of course, this is not new – but is also not the usual first preference. I am drawing more from data collection usually performed through actual physical interaction: such as doing case-studies, some form of ethnography, participant observation, interviews, or focus groups. So, I will be focusing on possible alternatives to these while on lockdown.

Technical matters

By now, most of us would have been exposed with using Zoom, Microsoft Teams, GoToWebinar, Qualtrix, various online forums. Or even going old school with Skype meetings, or the plain voice call altogether.

One cannot discount the potential usefulness of externally available data that may be used to triangulate with the data we collect from our remote interactions with individuals or organisations. Netnography as a method may also be of interest.)

Our pre-written topic guides, pre-COVID designed case protocols, and interview/focus groups’ instruments may not necessarily convert as smoothly onto digital platforms. So, we may need to consider revising them.

1 | Some alternatives (which may be obvious to some—and some of us probably have considered but not quite tested out yet)

- Video interviews/focus groups (via previously mentioned platforms)—although, make sure that the interviewees are comfortable with this. There are of course a number of things one will need to consider, such as the availability/reliability of technology. It would be good practice to ask participant(s) which platform they are familiar with. Offer them options. Another important issue is that, although most of the platforms allow for session video recordings, you must make sure you acquire consent from participants. You may find that some participants may be more welcoming of an audio recording than a video recording (as this is typically the case too, for face-to-face interviews).

- Audio only interviews/teleconference (via landline, mobile phone or an online platform). This option should always be offered to potential participants.

- Online surveys (most of you may be familiar with the different tools available, although qualtrics comes highly recommended by Nico Pizzolato; and is also in use for the CUSP CYCLES study.)

- Whichever approach one takes, we always have to make sure that ethics guidelines and GDPR are followed.

- There are a number of useful software and applications that help with the transcription and organisation of your data: I tend to use ai and NVIVO. Otter, the app, tends to transcribe as the interview is running and can work as a bolt-on with conference applications like zoom. It doesn’t necessarily convert speech to text perfectly, but it seems to learn commonly used jargon and improves the more it is used.

2 | Preparation is crucial: Do dry-runs

- Just as we would for running a “real-life” interview or focus group, make sure the instrument is taken for a dry-run. Testing interview instruments on peers, members of your family; basically anyone who may be able to relate to the topic you are looking at. It is about testing out whether the prepared questions/topics for discussion are intelligible and are sufficiently comprehensive for the set research objectives.

- Feasibility testing: make sure the technology works, whether it is the actual platform we are using to make contact, our recording device and how these work with each other. Make sure that there is sufficient memory capacity to complete recordings, and satisfactory bandwidth to run sessions. Investing in an external microphone can also be handy; as most of the built-in microphones tend to not produce the best output—so make it easier for our respondents to hear us better. Though, I also should point out that most of the current laptops/other portable devices tend to only have a headphone jack, so one may have to check for additional adapters or splitters to use external microphones.

- Always have a contingency plan. It may be that your “super-fast broadband” somehow keeps dropping out just as when you start your meetings, or your computer decides to do a random update. Secondary contact arrangements is recommended to be made prior to the interview/focus group sessions.

- Send digital invitations, these may be as emails followed up by calendar invitations. If we are using particular platforms, we have to make sure that this is specified in the correspondence. Again, check with the potential participants if they are comfortable with the arrangement.

- Depending on your type of work and who your participants are, the response rate for my meeting invitations tend to be better received as “virtual coffee” invitations. Just as I would in doing case study recruitments, I usually would invite the person who I consider as the gate keeper for the organisation for an informal chat over coffee. This can also be done virtually, though most of the time without you buying the coffee. It is however, probably not a bad idea to order some cake and coffee for them over eg Ubereats or Deliveroo… via offering a delivery gift card for example).

- Some individuals may request for different things prior to the remote meeting: such as

- Participant information sheet: detailing what the research is about. It is also recommended to give them an idea of how long the meeting will take. Informing our potential participants about how our work may be useful (or at the very least, interesting) for them is bound to increase the engagement/participation rate. Different institutions may have proformas for these, so make sure you update them for the approach you are taking for your research.

- List of potential discussion topics/questions: some participants may request for this prior to the remote meeting.

- Non-disclosure agreement or a confidentiality agreement between the researcher(s) and the organisation/persons one is setting up a session with. The institution one is with usually has proformas for these.

- A quick guideline for use of your chosen platform. Keep in mind that although your participant may have agreed to use zoom or skype, these platforms may not necessarily be ones they use regularly. Do offer to assist them in working out how these work.

3 | We may have to re-think our approach

- It is not just about using the same interview/focus group instruments as we would in face-to-face. As previously mentioned, we have to make sure that we are familiar and ready with whichever platform it is that we will be using.

- Keeping our interviewees or our focus groups engaged tends to be more difficult behind a screen (Just think about some of the online classes we have held since the abrupt transition, or those periodic departmental Zoom®/Microsoft Teams® meetings…). So, we have to make sure that we have a coherent flow during our meetings, as we will be the ones leading this. Us, as researchers, play an important role in driving the depth of our interview sessions. Some visual aids, or documents that can be shared instantaneously might be useful to encourage flow of our conversations.

- Pay even better attention to our participants—as your periphery is narrowed by what the camera lenses show on the other side, or what the microphone picks up on voice calls. These may have implications on the tone and depth of information exchanged, so may be worth keeping notes of. Our participants are most likely on lockdown, so just be mindful that there are likely a lot of other things occurring outside our allowed field of vision. Be prepared for interruptions.

- Allow more time pre and post our scheduled interview sessions, just as we would for normal face-to-face sessions. Some meetings may finish quicker than we expect, while some may last four times as long.

- As per usual, check ethics and the GDPR guidelines with relevant institutions.

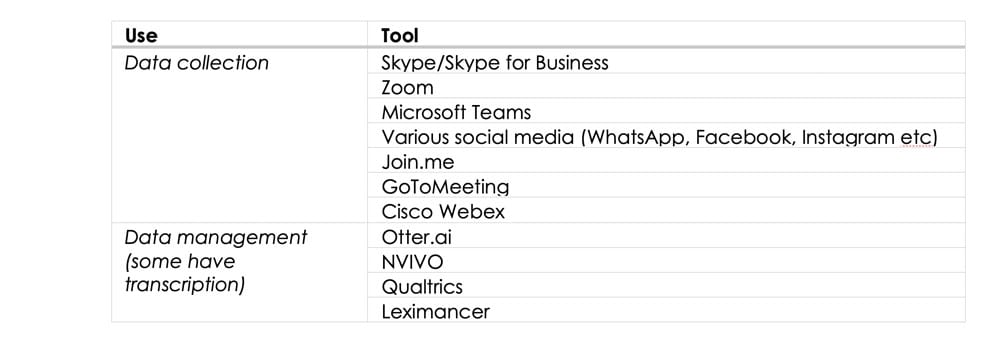

4 | Quick list of potentially useful apps/software, though not exhaustive. Also check the licenses your institution may have. I cannot emphasise enough – please check that whichever software/application is used and however data is collected and stored: that we are working within our institution’s ethics guidelines and GDPR.

There are no “good” and “bad” data—though, there may be not-so-good research.

Again, echoing David Silverman, our current situation calls for us to be methodologically inventive, yet still be empirically rigorous. In these unprecedented times, our work can be even more theoretically-vibrant, as well as practically relevant. It is safe to assume that whatever data we co-create will be influenced by the multitude contemporary challenges we are facing. Moreover, you may even be able to increase our reach for participants!

Take note of what is generally seen as “obvious” actions, sayings, settings, or events as these are all potentially remarkable—we are, after all, living in non-ordinary times.

Go forth into the field—online.

Doing field work is generally seen as “messy” work, this seem to hold truer when we remove closer physical proximity.

In this fairly short blog, I have suggested some alternatives to “traditional” qualitative data collection; though, as we know collecting data is not even half the battle.

So, we also have to make sure that we allocate sufficient time for rigorous data analysis—

Word of advice: do not underestimate the amount of time required for analysis, (and I am speaking from current experience!).