Careless Finance—Operational and economic fragility in adult social care

Christine Corlet Walker, Angela Druckman and Tim Jackson

CUSP Working Paper Series | No 26

Summary

Adult social care across the OECD is in crisis. Covid-19 has exposed deep fragilities which have combined to place unprecedented strain on social care organisations. Principal amongst these is the process of marketisation and financialisation of the social care sector. In this paper, we take a critical perspective on this process.

We argue that adult social care is ill-suited to being operated as a market, for four specific reasons. First, it has limited scope for labour productivity growth. Second, local authorities have the power to set prices unsustainably low. Third, there is an inherent lack of consumer access to information about price. Fourth, consumers have scant ability to express preference and exercise choice about providers.

These factors place social care in acute danger of predatory financial practices. In fact, we use primary data from the financial accounts of the five largest UK care home chains to show how debt-leveraged buyouts, intra-group loans, offshore ownership and sale and leaseback arrangements have combined to create a clear moral hazard that is having a devastating effect on the most vulnerable in society.

Financial engineering represents an explicit strategy to shift costs, socialise risks and privatise the benefits of investing in social care. In the process, marketisation has facilitated the conditions for both financial fragility and operational failure.

We argue that post-pandemic recovery represents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to overhaul these conditions and transform adult social care.

1. Introduction

Adult social care (or long-term care) sectors[1] across the OECD are facing multiple structural, financial and political challenges. Most are meeting a precipice of rising care needs as a result of their aging populations (Colombo et al., 2011; Kingston, Comas-Herrera and Jagger, 2018). For some, this baseline challenge has been exacerbated by political decisions to pursue austere economic policies in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis (Van Gool and Pearson, 2014; Janssen, Jongen and Schröder-Bäck, 2016; Gori, 2019); a strategy that has now been largely condemned as economically and socially damaging (Stuckler and Basu, 2013; Loopstra et al., 2016; Stuckler et al., 2017). Further, the growing involvement of private equity in the residential and nursing homes market (Knight Frank, 2020; Savills, 2020; UNI Global Union, 2020) has created ongoing concern about the economic sustainability of the sector. Covid-19 has exposed the depth of the vulnerabilities created by these conditions, with some authors arguing that a combination of limited planning attention from governments (compared to acute medical settings), pre-existing economic fragility, and a “deep rooted devaluation of care work” has contributed to the large proportion of Covid-19-related deaths that have occurred in care home settings (Faghanipour, Monteverde and Peter, 2020, p. 1171; Szczerbińska, 2020).

The UK’s adult social care sector has experienced the extremes of many of these challenges, and those working and living in the sector have been saying that it is in crisis for many years (Bunting, 2020). Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, the industry regulator—the Care Quality Commission (CQC)—reported that 16% of care homes in England were rated inadequate or requiring improvement (CQC, 2020). At least 1.5 million people aged 65+ in the UK are reported to have some level of unmet care needs (Age UK, 2019b); that is approximately 8% of over 65s. Meanwhile, data from Public Health England shows that the total number of residential and nursing home beds, per 100 people aged 75+, declined between 2012 and 2020 by 15% and 10% respectively (Public Health England, 2020a). On the staffing side, according to Skills for Care, in 2019 there were more than 120,000 vacancies across the sector, a staff turnover rate of more than 30% percent, and almost a quarter of the workforce were on zero-hours contracts (Dave et al., 2019). Further, care work is one of the lowest paid sectors in the economy. By March 2020 the median hourly pay for care workers was £8.50, just 29p above the National Living Wage[2] (Fenton et al., 2020). As a result, job satisfaction among carers is low, and declining (Nuffield Trust & The Health Foundation, 2019).

These structural problems have been, and are likely to continue to be, exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, which has hit care homes particularly hard. Between March 2020 and January 2021, care homes across the UK registered almost 20,000 deaths linked to Covid-19 (ONS, 2021)—almost 5% of the total care home population—with 15,476 care homes reporting at least one outbreak up to July 2020[3] (Public Health England, 2020b). In the midst of the third peak in January 2021, snapshot industry surveys indicated rates of staff absenteeism as high as 50% in some care homes, as a result of “Covid-19 positive case[s] being picked up by PCR testing, self-isolation following contact tracing, shielding and childcare responsibilities” (NCF, 2021). Through all this, the risk of care home closure and rising levels of unmet need only grows.

Many of the problems surrounding resilience in the social care sector have been traced back to the consistent regime of austerity inflicted by sequential governments since the 2008 financial crisis. Taking into account the impact of an aging population, The Health Foundation estimates that “spending per person on adult social care services fell by around 12% in real terms between 2010-11 and 2018-19” (Gershlick et al., 2019; Foster, 2020). As a whole, the social care sector receives almost half of its annual income from local authority funded residents (Kotecha, 2019), making it highly vulnerable to government spending cuts. Consistently inadequate funding has squeezed the social care sector to a point of significant economic fragility (Bottery, 2019), particularly in the context of rising costs to care home providers associated with Covid-19 infection control measures. Despite Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s repeated promises to reform the social care sector (Johnson, 2019, 2020), the latest budget statements (Chancellor of the Exchequer, 2020, 2021) do little to assuage fears that social care is being deprioritised, underfunded, and forgotten, yet again.

However, a lack of sufficient public funding can only tell us half the story about why the adult social care sector is so economically fragile and crisis prone. One area that has not received as much attention in public and policy discourse is the role of financialisation in creating the conditions for fragility within the sector. Financialisation describes the increasing influence of financial institutions, markets and elites within a particular sector. Its effect is to “ (1) elevate the significance of the financial sector relative to the real sector; (2) transfer income from the real sector to the financial sector; and (3) contribute to increased income inequality and wage stagnation” (Palley, 2008, p. 1). As we will discuss in more depth later, financialisation is widespread in the adult social care sector, with private equity owned care home chains now responsible for approximately 50,000 care home beds (CQC, 2021), and those chains that exhibit some at least form of financial engineering responsible for even more. In total, 10% of the sector’s £15bn annual income “leaks out… in the form of rent, dividend payments, net interest payments out, directors’ fees, and profits before tax” (Kotecha, 2019, p. 4).

This growing financialisation is taking place in the context of long-term trends of increasing inequality (Denk and Cournede, 2015; Ruiz and Woloszko, 2016), stagnating economic growth rates in wealthy economies (Jackson, 2019), and a persistent inability to rapidly decouple economic growth from greenhouse gas emissions and broader environmental impacts (Hickel and Kallis, 2019; Jackson and Victor, 2019; Parrique et al., 2019). The details of how this financialisation plays out in the coming months will have an impact on the shape of the post-Covid-19 social care landscape, particularly in terms of the distribution of ownership, accountability and transparency of public funding, and quality of care and working conditions across the sector. As the prospects for economic recovery remain unclear (IMF, 2020, 2021) there is an urgent need to understand the financial structure of the social care sector, to identify who is capturing the already scarce revenue growth, and to explore how we can create a sector that is economically resilient and socially just; meeting the needs of all within the means of the planet.

In this paper we take a political economy approach to exploring the structures of marketisation and financialisation within the UK’s adult social care sector. We pay particular attention to the distribution of power and wealth, as well as the links between the economic and the “political, technological, social, [and] historical” (Anderson, 2004; Mattioli et al., 2020, p. 3). In Section 2, we argue that social care is poorly suited to being operated as a market owing to several core characteristics of the sector. In Section 3, we turn to the financial structure of the social care sector, presenting primary data from the financial accounts of the five largest care home chains in the UK. These demonstrate the range of financial engineering tactics in place within the companies. In Section 4, we discuss evidence of the impacts of financialisation on quality of care. We highlight the need for research looking at the relationship between specific financial engineering practices and key sector outcomes. In Section 5, we conclude by arguing that financialisation has created the conditions for financial and operational fragility within the sector. It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss alternatives to the current marketised and financialised structure of adult social care. However, our political economy analysis identifies potential leverage points for change and makes the case for transformation more urgent.

2. Marketisation of adult social care

Social care markets were introduced across the UK by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government through the enactment of the National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990. The act turned away from publicly-run social care, towards the tendering out of services to private and public providers alike, and commissioning based on a mix of social, political and economic aims (Knapp, Hardy and Forder, 2001). This shifted the role of local authorities from providers of social care, to brokers, care managers, purchasers and regulators (Wanless, 2006; Barron and West, 2017). Private, for-profit firms now own and manage 84% of adult social care beds in the UK (Blakeley and Quilter-Pinner, 2019); the inverse of the 1980s, where more than 60% of beds were run by local authorities or the NHS (Bayliss and Gideon, 2020). However, we argue here that the adult social care sector is poorly suited to being operated as a market for several key reasons, detailed below. Several other countries have similar marketised systems, including the US, Sweden and Australia (Stevenson and Grabowski, 2010; Brennan et al., 2012), and many of our arguments can also be applied to these contexts.

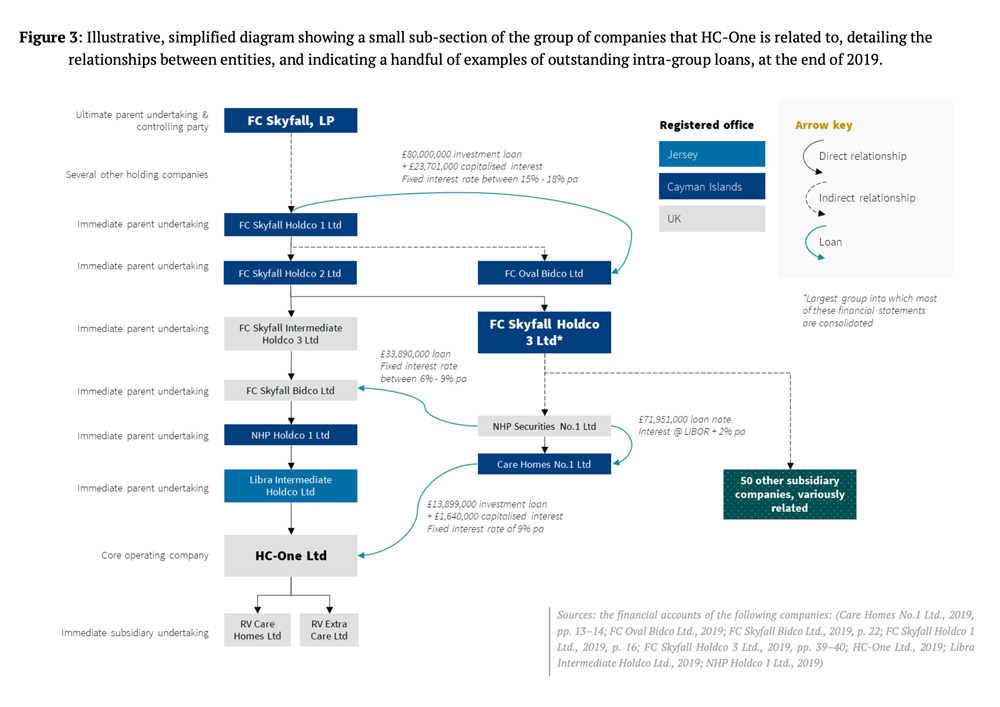

In 2014, a new Care Act was introduced in the UK which states explicitly that it is the duty of local authorities to “promote the efficient and effective operation of a market in services for meeting care and support needs” (Care Act 2014, 2014, p. 5). In fact, this ‘market in services’ is most accurately described as a ‘quasi-market’ because it contains both for-profit, commercial providers as well as non-profit, voluntary and public sector providers (Bartlett and Grand, 1993). Additionally, some of those purchasing services are not private individuals but public bodies acting on behalf of consumers (i.e., service users[4]) (Barron and West, 2017). Approximately 37% of the 454,000 available beds are fully-funded by local authorities in the UK, and a further 12% are part-funded (CMA, 2017b). See Figure 1 (above) for a simplified schematic of the types of relationships that characterise the UK’s social care market. It is the specific structure of this quasi-market that begins to explain why the social care sector is so poorly suited to being operated as a market. We argue that there are four core characteristics of the UK’s social care sector (which it shares to a varying extent with other social care systems across the OECD) that combine to create a ‘dysfunctional’ market that serves neither its financial nor social aims effectively. These are: 1) the limited scope for labour productivity growth; 2) the power of local authorities to set prices unsustainably low; 3) the lack of consumer access to information about price; and 4) the inability of consumers to freely express their preferences between care providers. We discuss each in turn below.

Competition is a metric that is often associated with market functionality. Higher levels of purchaser and supplier competition are taken to be broadly synonymous with improved market efficiency. For example, the UK Government’s Office of Fair Trading (established 1973; disbanded 2014) argues that “effective competition in properly regulated markets can deliver lower prices, better quality goods and services and greater choice for consumers” as well as creating “strong incentives for firms to be more efficient and to invest in innovation, thereby helping to raise productivity growth” (Office of Fair Trading, 2009, p. 6). However, taking a closer look at the data from the UK care homes market, Forder and Allan (2014) demonstrate that regions with higher levels of competition among providers are associated with lower quality care, mirroring findings from the US (Castle, 2005; Bowblis, 2012). This is in contrast to theoretical understandings about the role of competition, which would anticipate an increase in innovation and product quality in response to higher levels of competition (Hunt and Morgan, 1995). So why do the dynamics of competition and quality not behave in the expected way in the adult social care market?

Turning to our first characteristic of interest, we consider the ease with which actors in the sector can respond to increases in competition by improving the cost-effectiveness with which they produce their good. The evidence on economies of scale within adult social care is mixed (often depending on service type and care needs) and where it is found, it is usually modest (Christensen, 2004; Barron and West, 2017, p. 139). There is also limited scope for cost-efficiency gains from increasing labour productivity (Jackson, 2017, p. 174). This is because the main input for the production of the service is time spent with a care worker. Staffing costs are the largest line item of most care homes, often making up more than 60% of operating costs (Burns et al., 2016; Horton, 2019). The scope for reducing this cost without compromising the service is limited. Reducing costs through a downward pressure on wages is likely to be counterproductive in a sector where 58% of care workers are already paid at or just above the National Living Wage (the legal minimum for over 25s) (Fenton et al., 2020). Perhaps more crucially, although technological advancements can usefully reduce time spent doing repetitive tasks—such as administration, logistics, etc.—reducing the time that a care worker spends with a resident (i.e. increasing their productivity) is likely to reduce the perceived quality of care delivered, rather than increase it. Together, these conditions constrain the pace of, and scope for, labour productivity gains in the sector. In fact, labour productivity in adult social care has fallen by more than 10% in the UK since 1997 (ONS, 2020).

This feature in itself need not necessarily generate a downward pressure on quality in the sector. However, coming to our second characteristic of interest, local authorities are the dominant purchaser in the market, buying services on behalf of many individual service users. This means that they have significant market power and hold the ability to set prices at a lower level than they would be in a demand-competitive market. Between 2010 and 2015 there was a real term reduction in local authority social care spending of 17% and expenditure had still not recovered to 2010 levels by 2019 (The King’s Fund, 2020). In the context of cost-minimising behaviours by local authorities (Rubery, Grimshaw and Hebson, 2013), this funding constraint has likely been responsible for driving prices to an unsustainably low level. In response, some care home providers have even “exit[ed]” the local authority funded segment of the market (CMA, 2017a, p. 6). However, since care homes generally require high occupancy levels to break even (often more than 85% occupancy; Burns et al. 2016), and given that local authority contracts represent a large portion of demand, providers are often coerced into accepting low prices, which in some cases might even be “below the marginal cost” (Hancock and Hviid, 2010; Allan, Gousia and Forder, 2020, p. 7).

Our third characteristic of interest is the lack of information available to private paying consumers (aka self-funders) about the price and quality of care supplied and purchased in the market (Chou, 2002; Grabowski and Town, 2011). This informational asymmetry gives social care providers market power over private payers, since acquiring the relevant information would entail significant “search costs” (Allan, Gousia and Forder, 2020, p. 7). When combined with a complex market structure in which local authority intermediaries buy on behalf of a large number of service users, this feature enables the development of significant price discrepancies between privately and publicly funded care home beds, even “for the same level of accommodation and service” (Wanless, 2006, p. 98) . According to the Competition and Markets Authority “the average cost for a self-funder in 2016 was £846 per week… while LAs on average paid £621 per week” (CMA, 2017c). As a result, those middle- and working-class families who do not meet the eligibility criteria for state support, but who cannot afford to pay for a place at a ‘private payer only’ care home, end up effectively subsidising publicly funded residents. Since the details of local authority contracts with care homes are not publicly available, providers have no need to justify the higher prices they are charging to private paying residents. The opacity of the system also benefits local authorities as they are not forced to renegotiate prices with providers to better reflect the market average. However, if private payers cannot afford these higher prices, and if eligibility criteria remain punitively stringent, this can result in a gap in provision. Indeed, Age UK report that 1.5 million older people in England are not receiving the help they need with essential everyday tasks such as “washing, dressing and using the toilet” (Age UK, 2019a, p. 4; Foster, 2020).

How, then, do these conditions—low or negative productivity growth, unsustainably low price-setting by local authorities, and informational asymmetries—affect the quality of care provided across the sector? In theory, as competition increases, consumers (or service users) have more choice between providers. This should then translate into pressure on those providers to innovate in order to deliver better quality care for the same price (or the same quality for a better price). This theoretical relationship is one of the primary motivations behind the outsourcing of public services and, more specifically, the move from state-run social care to a quasi-market (Girth et al., 2012; Barron and West, 2017). As we have already outlined, providers’ ability to improve the quality or cost-effectiveness of the care they provide may be dampened by limited scope for labour productivity growth and price-setting by local authorities. Additionally, in order for competition to reliably lead to an increase in quality of care, service users must be able to respond to the increased choice and act on their preferences between providers. Crucially, this depends on 1) their ability to “evaluat[e] the quality of provision” delivered by different providers, and 2) their ability to “transfer… out of a facility that they find inadequate once they become resident there” (Barron and West, 2017, p. 144).

This brings us to the final characteristic that cements the status of social care as unsuitable for marketisation: the inability of service users to effectively express their preferences between providers. Individuals are often distressed when they enter the social care market; the move into a nursing or residential care home may be in response to a family death, the disruption of existing support networks, or declining personal health (Forder and Allan, 2014; Barron and West, 2017). This means that even if information about price and quality are available, the search for a place at a care home may be rushed because the personal cost associated with waiting is too high. In these cases, proximity and timing become priority factors over quality and value for money. Further, once an individual has been placed in a care home, they may not be able to act on their preferences or respond to changes in the quality of the service over time. This is because moving from one care home to another can entail significant physical and emotional costs (or ‘transaction costs’), also known as “transfer trauma” (Grabowski and Hirth, 2003, p. 3). This is reflected in low recorded absolute rates of transfer between nursing homes in the US, for example (Hirth et al., 2003). Even when someone is moved to a different care home, this is often in response to regulatory issues around permitted types of care provision, rather than consumer preference (Reed et al., 2003). The ‘stickiness’ of these consumers confers significant market power onto providers. This means that providers can more easily express their own preference for profit over quality of care without being penalised by declining occupancy levels. Notably, however, this downward pressure on quality is theoretically only possible down to the minimum quality standards set by the CQC, below which a care home might be put into special measures or closed.

Through these dynamics we can see how the market structure of social care in the UK enables the prioritisation of financial goals by providers, often at the direct expense of the quality of care provided. The evidence that for-profit ownership of care homes is related to worse quality care and poor working conditions is compelling (Hillmer et al., 2005; Comondore et al., 2009; Burns et al., 2016; Burns, Hyde and Killett, 2016; Barron and West, 2017). A meta-analysis by Comondore et al. (2009) found that for-profit homes across Australia, Canada, Taiwan and the US had 0.42 fewer staff hours per resident per day. In the UK, Barron and West (2017, p. 137) found that “for-profit facilities have lower CQC quality ratings than public and non-profit providers”. Further, wages in for-profit care homes are reported to be on average £2 per hour lower than in publicly run care homes (Burns et al., 2016). Interviews and observations at care homes across the UK also found that poor pay was often compounded by a raft of strategies designed to reduce costs, such as “restricting annual leave, reducing the numbers of qualified nursing staff, increasing resident: staff ratios, removing sick pay, moving to unpaid on-line training to be completed at home, removing paid breaks and no longer paying for handover meetings at the start and end of shifts” (Burns et al., 2016, p. 25; Burns, Hyde and Killett, 2016).

None of the characteristics laid out above are necessarily a problem alone, and many well-functioning markets exhibit one or more of them. However, in combination they result in several dysfunctional dynamics, including downward pressure on service quality, wages and working conditions, and a gap in provision for many older people in need. Some of these ‘dysfunctional’ characteristics may even be perceived as a source of value for financial investors, who can take advantage of their power over consumers and workers in order to extract the maximum amount of value. Certain targeted ‘fixes’ might enable the market to operate more effectively for consumers, intermediaries and providers. For example, improving the availability of information about price might encourage an equalisation of private and public fees (although this outcome is far from certain). However, sticky consumers and the limited scope for labour productivity growth are more pernicious challenges that are likely to be more difficult to ‘solve’.

3. Financialisation of adult social care

The marketisation/ privatisation of social care has acted as a doorway to the increased involvement of financial entities in adult social care across the UK and elsewhere over the last three decades, and has culminated in “three of the five largest [UK] chains” now being owned by private equity (Burns et al., 2016, p. 18). In turn, the largest eight private-equity-owned care companies are responsible for approximately 12% of care home beds across England (authors’ own calculations from CQC care directory data; CQC, 2021). In the US, Sweden, and Norway, private equity investors also own several of the largest care home chains (Harrington et al., 2017). Naturally, industry narratives around private equity emphasise its “social benefits” (Froud and Williams, 2007, p. 2)—e.g. employment and productivity growth, opportunities for impact investing, etc. (BVCA, 2006, 2021; AVCAL, 2007)—as well as its enhanced “operating performance” and the generation of “economic value” (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2009, pp. 130, 132). However, the emergence of several reports detailing the structure of the financialised parts of the social care system, and tracing the flow of money through that system (Burns et al., 2016; Kotecha, 2019; Bayliss and Gideon, 2020), do not indicate a commitment to care and to the quality of life of those living and working in the sector. Rather, they suggest a strong prioritisation of financial over social goals, often indicating the pursuance of the former at the direct expense of the latter.

Over the last 30 years, the financialisation of social care in the UK has been characterised by large-scale buyouts of social care organisations by financial entities, such as private equity firms and wealthy individuals (Horton, 2019). Since the involvement of these financial entities, high expected rates of return-on-investment (ROI) of at least 12% have been the norm[5] (Laing, 2008). However, ROIs in this range are more common in “highly risky” markets, characterised by “severe cyclicality, rapid technological change etc.”, none of which applies in any meaningful sense to the social care sector (Burns et al., 2016, p. 30). This is important because the higher the expected return, the more the profit margin is squeezed as labour (and other costs) come directly into competition with returns to investors. In a sector that has low scope for labour productivity growth, this tension has the potential to translate into a downward pressure on wages. Further, the higher the expected return, the more financial engineering tactics (such as asset stripping) are likely to be used to try to increase return to investors in the short-term, potentially posing risks to the long-term sustainability of the acquired social care organisations. We explore these dynamics, and the role of private equity in particular, below.

Private equity can be understood as a “rearrangement of ownership claims” in the service of “value capture and value extraction” by a relatively small number of individuals (Froud and Williams, 2007, pp. 2, 4). Indeed, financialised social care organisations in the UK and the US have been found to use a range of strategies that reduce tax obligations and maximise value extraction for the benefit of investors and fund managers (Harrington et al., 2011; Burns et al., 2016; Bayliss and Gideon, 2020). We consider these strategies, in part, to be a dysfunctional outcome of a marketised social care sector. Concerns about their implications are wide-reaching, from their effect on wealth inequalities and the lack of financial transparency, to their impact on the resilience of individual firms and even the economic stability of the whole sector (Froud and Williams, 2007; Palley, 2008; Pradhan et al., 2013). In their landmark report, Burns et al. (2016) explore the most commonly used tactics in the UK’s social care sector. These include: 1) debt-leveraged buyouts; 2) intra-group loans; 3) the use of offshore tax havens; 4) splitting the operating and property companies; and 5) sale and leaseback arrangements (a form of asset stripping). Below, we give an overview of how each of these tactics works. We then explore some specific examples from the five largest care home providers in the UK.

3.1. Financial engineering tactics

Beginning with debt-leveraged buyouts: when a private equity firm buys a social care company, or any company for that matter, they must raise the funds to do so. This is usually done through a private equity fund, which is managed by the private equity firm, aka “the sponsor” (Rosenbaum and Pearl, 2009, p. 161). Third-party investors[6] provide most of the investment capital for the fund, which the sponsor then invests. In a debt-leveraged buyout, the funds to buy the target company (e.g. the social care company) come in part from this private equity fund, and in part from a loan package[7]. The ratio for debt-leveraged buyouts (LBOs) has historically been “60 to 90 percent debt” to 10 to 40 percent equity (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2009, p. 124). Normally, the loan is secured against the assets of the acquired company, and debt-repayment becomes the liability of the acquired company also (Sherwin, 1988). This means that the group of investors financing the loan package have claim to the target company’s assets in the event that it becomes insolvent (i.e. unable to service its debts). In the case of a social care company, the loan will likely be secured against the care home properties. Further, if the target company is publicly traded pre-acquisition, when the private equity firm buys it, it will typically be ‘taken private’. This means that the company is removed from the stock exchange, such that its shares can no longer be freely traded, and it becomes a privately owned company.

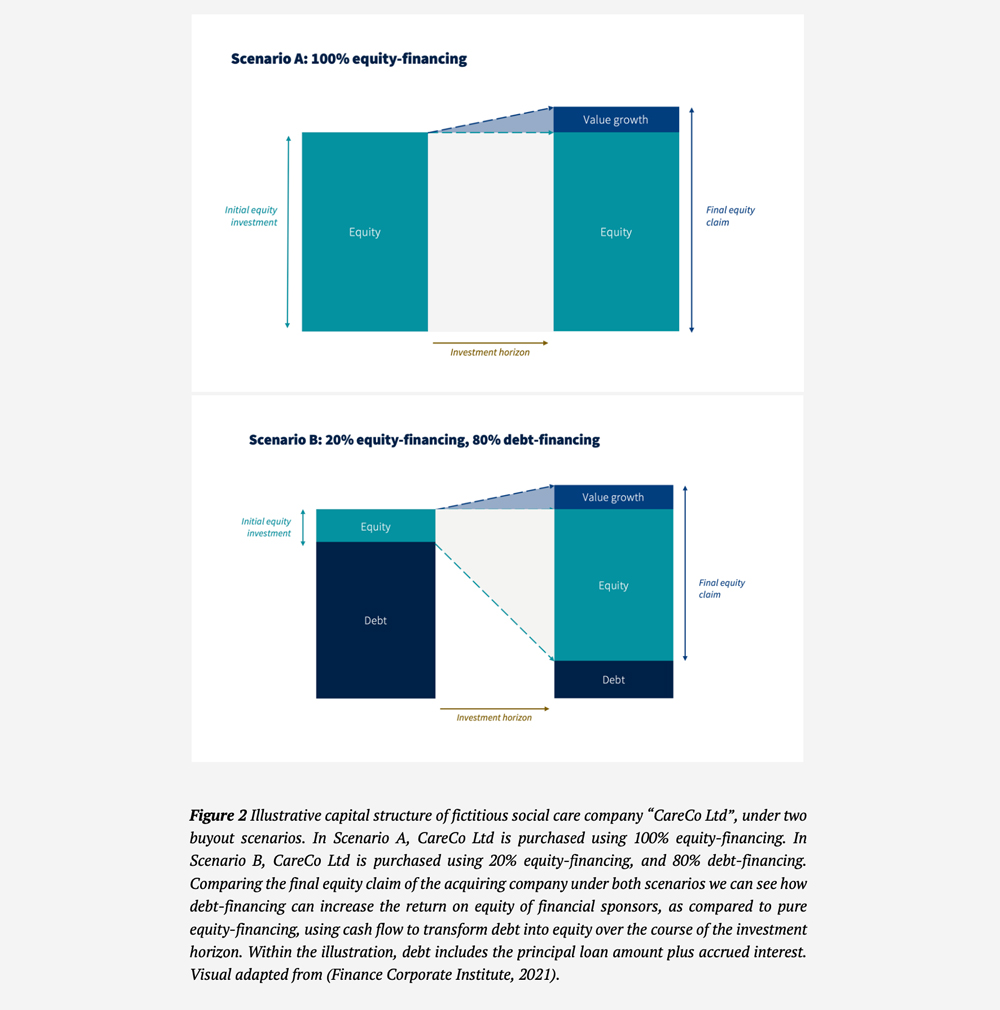

There are many motivations for LBOs (e.g. the ability to carry out very large deals that require a significant amount of upfront capital). One motivation of interest is the desire to increase the rate of return on the private equity fund investment. This happens in two main ways. First, since the sponsor puts up only a small proportion of the money to buy the company, with the rest of the purchase price being covered using a loan, the capital structure of the target company just after acquisition is skewed heavily towards a high proportion of debt and low proportion of equity. Over the course of the investment horizon, then, the target company’s cash flow can be used to “service and repay debt” (Rosenbaum and Pearl, 2009, p. 162). As this happens, the equity portion of the company’s capital structure gradually increases (Rosenbaum and Pearl, 2009), since equity equals assets minus liabilities. For example, a private equity firm might pay 20% of the price of acquisition of “CareCo Ltd” (fictitious social care company) using capital from their private equity fund, and cover the other 80% with debt-financing. As CareCo Ltd uses its cashflow to repay the principal and the interest on the debt, the equity portion of their capital structure will grow. Since the private equity firm owns CareCo Ltd, this translates to a potentially sizeable return for them and their third-party investors on exit (when CareCo Ltd is sold or its shares offered to the public). This is likely to be much larger than the return derived through company growth alone (i.e. what would be earned if investors bought the company using 100% equity)[8]. See Figure 2 (below) for an illustration of this principle.

Second, the tax-deductible status of interest payments offers a “tax shield” (De Maeseneire and Brinkhuis, 2012, p. 161), which further improves returns to equity, proving highly valuable for some firms (Kaplan, 1989; Kaplan and Strömberg, 2009, p. 134). Burns et al. (2016, p. 23) highlight how advantageous these kinds of changes to capital structure can be, with Care UK reducing their tax payments by “some £25 million a year in 2012-14” through a shift towards debt-financing. In these ways, debt-leveraged buyouts can be understood as a form of rent seeking; i.e. the “expenditure of resources and effort in creating, maintaining, or transferring rents” (Khan, 2012). In other words, LBOs constitute (in part) an investment in the transfer of wealth to investors through a redistribution of existing economic resources, without necessarily generating any new wealth. They can also contribute to a concentration of rentier power; either by taking a publicly-traded company private (so it is no longer traded on the stock exchange), or by acting as part of a “roll-up” mergers and acquisitions strategy to consolidate ownership across the market (Rosenbaum and Pearl, 2009, p. 169).

The social care sector is messy, with a variety of company sizes, capital structures, and local commissioning landscapes. However, given due diligence on these fronts, certain social care companies may make appealing LBO targets because of their large asset base, stable cash-flow (thanks to the stability of the ageing population and the legislative duty of local authorities to source social care for their residents), and opportunities for ownership consolidation as older “mom and pop” care homes are expected to exit the market (Brill et al., 2015, p. 75). Each of these characteristics mean that the target company is more likely to be able to service the substantial debt payments, to be stable over the course of the investment horizon, and to offer opportunities for growth (Rosenbaum and Pearl, 2009). However, the flip side is that the LBO may pose a risk to the long-term stability of the target social care company as a result of the likely significant reduction in its financial flexibility (De Maeseneire and Brinkhuis, 2012, p. 156), which could ultimately affect resale value.

Intra-group loans and the use of offshore tax havens form another mechanism for increasing returns to investment. According to a forensic accounting study from the Centre for Health and the Public Interest, across the adult social care sector in 2017, £117m in interest payments were made to companies that were related via corporate group structures (Kotecha, 2019, p. 4). That is 45% of total interest payments made by the sector that year. This reflects the prevalence of intra-group loans within these corporate groups; i.e. loans from one related subsidiary company to another. Sometimes these loans happen between companies that are related, but located in different tax jurisdictions (e.g. a UK-based subsidiary company might receive a loan from a related company that is located in Jersey). Through the servicing and repayment of the debt, money can be moved from group subsidiaries registered in the UK, to those registered in offshore, low tax jurisdictions (tax havens). This strategy offers corporate group owners several advantages. First, as with LBOs, the tax-deductibility of interest payments can reduce tax obligations for the UK-registered company. Second, setting artificially high interest rates on the loans (15% or more) allows rapid cash extraction to low tax jurisdictions, thereby increasing the return to owners since both companies are likely owned by the same ultimate controlling party. This advantage can also be achieved using some mix of “administration charges, licensing arrangements or royalty payments” (Burns et al., 2016, p. 14). The total leakage to offshore companies via these means has to our knowledge not been calculated for the UK. However, we can expect it to be a potentially significant sum since, for the largest 26 care home providers, those providers with an owner in a tax haven paid on average more than three times as much in net interest payments as those providers who did not have an owner in a tax haven (Kotecha, 2019, p. 11).

Another financial engineering strategy commonly used by the largest for-profit care home providers is to split the care home operating and property companies from one another. This usually involves a sale and leaseback arrangement in which properties are sold off on the agreement that they are subsequently leased back to the operating company (Horton, 2019). This offers one of two potential benefits to company owners. If the properties are sold to an external party, this enables the care home chain owner to gain a large quantity of cash upfront to pay “special dividends” to shareholders (Pendleton and Gospel, 2014, p. 18) or to rapidly expand the business through acquisitions (Burns et al., 2016, p. 23). Alternatively, if the properties are bought by a related company, it enables the owner to extract cash from the operating business to the related property company on an ongoing basis by charging high rents, in some cases with guaranteed annual rental increases “in excess of market norms” (Pendleton and Gospel, 2014, p. 27). Again, these property companies are sometimes based in “offshore jurisdictions” (Bayliss and Gideon, 2020, p. 31). One of the impacts of these sale and leaseback arrangements is that the 18 largest for-profit social care providers spend “£11.07 out of every £100” of income on rent, where the eight largest not-for-profit providers spend just £2.34 (Kotecha, 2019, p. 37).

Combined, these tactics are aimed at maximising return on investment for owners through: the use of LBOs to increase investors’ return to equity; reducing tax obligations in high tax jurisdictions; ongoing cash extraction to low tax jurisdictions; and increasing the value of the company so it sells for a higher price at the point at which the investor exits. Many of these practices (and others, such as the issuing of preference shares) even ensure that owners can extract cash “whether or not the company is profitable” (Burns et al., 2016, p. 24). They can be understood as a transference of risk “from investors to other actors” (Horton, 2019, p. 8) and, in the extreme, these practices can leave the base social care operating companies over-leveraged, asset poor (as a result of both underinvestment and asset stripping), economically fragile and at “increased risk of failure” (Burns et al., 2016, p. 32).

3.2. Case studies

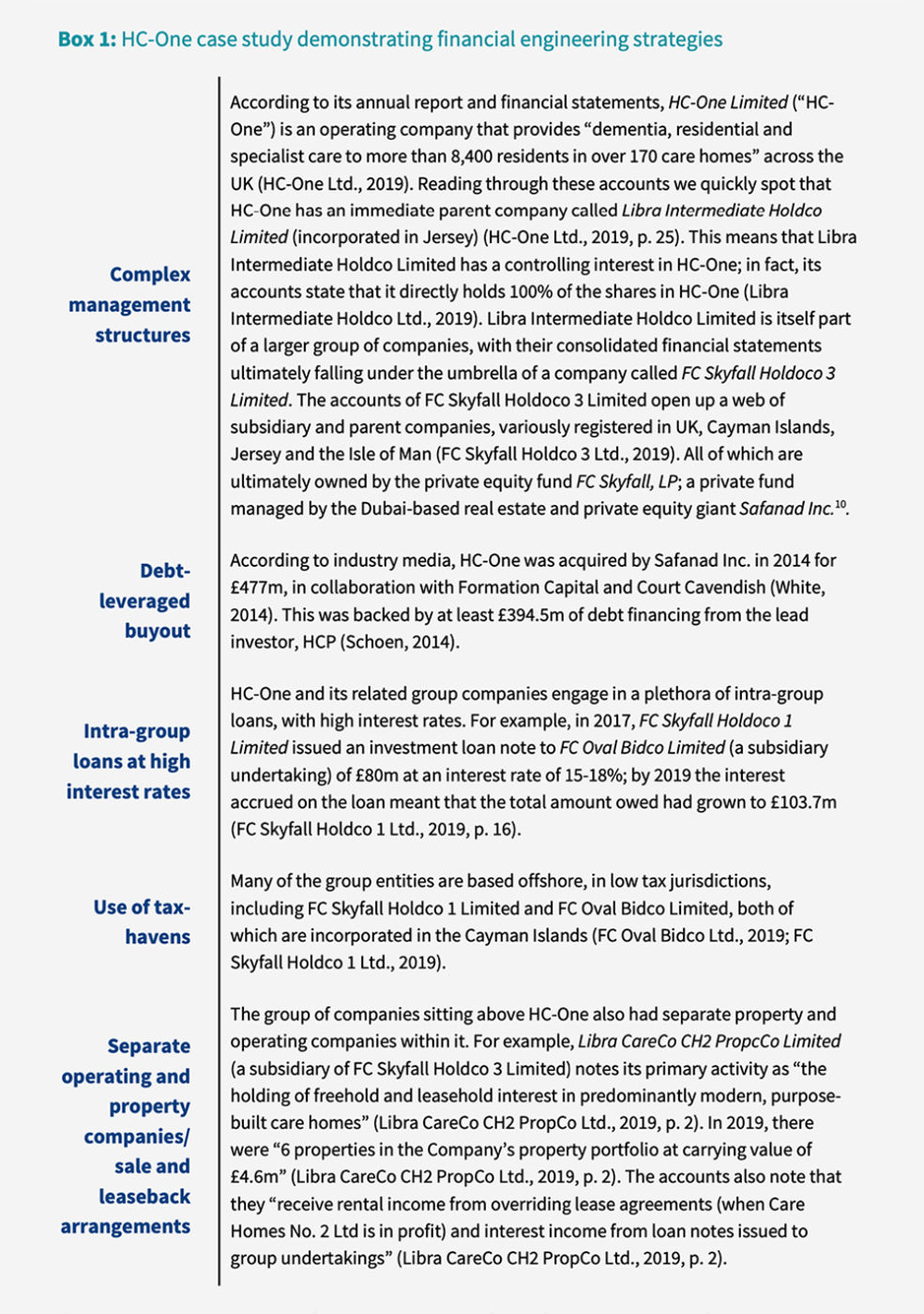

To bring these issues to life, we walk through the financial engineering strategies used by one of the UK’s largest chain care home providers, HC-One Limited. This is followed by a summary of how the same or similar tactics are also used across the other four largest UK care homes chains: Barchester Healthcare Limited, Four Seasons Health Care Limited, Care UK Limited, and Bupa Care Homes. We collected primary data from the annual financial accounts of each of these five care home chains; all of which were downloaded from the Companies House database (Companies House, 2021). We did this for both the main operating company and for a selection of relevant, related companies. See Appendix A for a full list of accounts used in the analysis and links to source documents. Notably, we did not collect data from all subsidiaries registered underneath the ultimate parent company for each of the five company groups. The goal of our exercise is not to calculate the total scale of the money being moved through these strategies; that has been done more completely elsewhere (Burns et al., 2016; Kotecha, 2019). Instead, our goal is to provide tangible, specific examples of each of the financial engineering techniques used by these care home chains, and to point the reader towards the primary data. In pursuit of this goal, we extracted the following information from each set of accounts: primary activity of the company; incorporation location of the company; names of related companies and relationship type (e.g. parent/ subsidiary); loans to related companies (including amount, date and interest charged).

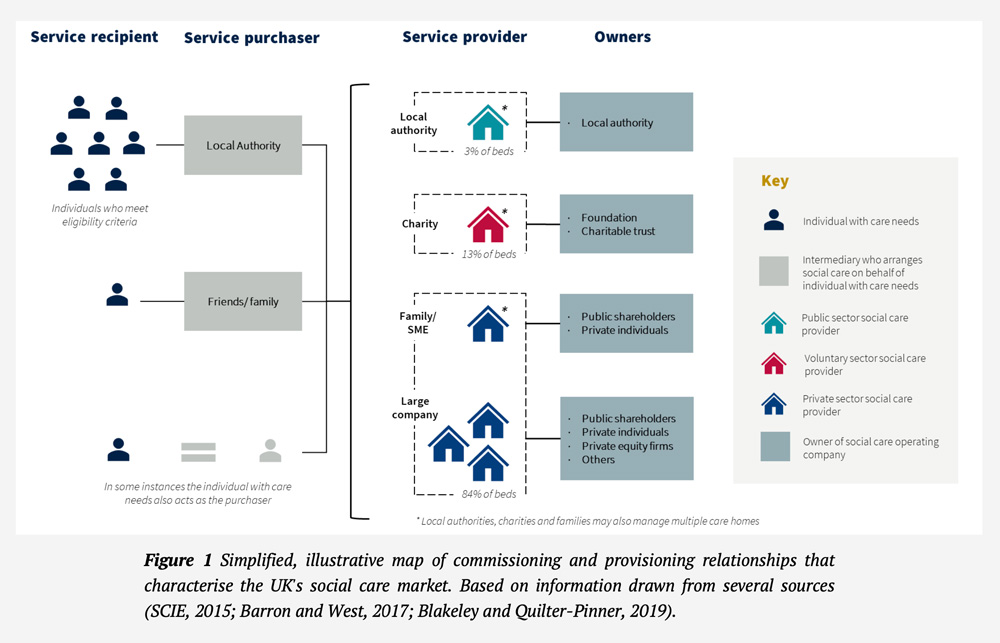

Turning to our first example, HC-One and its related companies demonstrate a number of financial engineering tactics of the kind described in Section 3.1 above. We give a small handful of examples in Box 1 below, visualising them where appropriate in Figure 3[9]. Although we do not know the intentions behind the development of these financial structures, we can clearly see the potential for significant tax savings and value extraction for owners via these mechanisms. In particular, there is evidence of large sums of money being moved through the complex company structures sitting above HC-One, often via intra-group loans with high interest rates, or via rental payments, and often to entities that are based in low tax jurisdictions. We complete a similar analysis for the other four largest care home providers in the UK, finding that all of them demonstrate some combination of the approaches described above. We detail specific examples of each financial engineering behaviour in Table 1, below. Again, these examples cannot tell us how much money is being moved in total by these organisations, or the objectives behind the development of the structures. However, they can at least demonstrate that the architecture is there for cost shifting, reducing tax obligations and extracting value.

4. The impact of financialisation on quality of care

Having established their existence, the obvious next step is to ask: how do these financial engineering strategies impact quality of care, working conditions and other important outcomes for the sector? Research looking at the impacts of financialisation and private equity ownership, over and above the effects of for-profit ownership, presents a mixed picture. The evidence is largely focused on nursing homes (not residential) and is highly US-centric. Among these studies, researchers have found a range of effects. Some studies reported differences in specific measures of care quality—such as reduced staffing intensity, lower staff skill-levels, and higher numbers of deficiencies—between private equity owned nursing homes and those owned by other for-profit firms (Harrington et al., 2001, 2012; Pradhan et al., 2014; Gupta et al., 2021), whilst others did not (Stevenson and Grabowski, 2008; Huang and Bowblis, 2019). A longitudinal case study by Bos and Harrington (2017) found that the impact of private equity buyouts on nursing home quality is not universal. Instead, it is likely linked to specific management strategies pursued around staffing levels, asset management and company restructuring, among other things. This is consistent with Burns, Hyde and Killett (2016, p. 1006), who found that the main financial pressures that lead to reductions in care quality and working conditions in private-equity-owned homes in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis were (alongside cuts to local authority budgets) “rental payments and efficiency measures”.

This highlights one of the main issues with the literature, to date. Whilst certain studies try to isolate the effect of private equity ownership on quality of care, they are often missing an embedded view of why private equity firms might be detrimental to quality of care. It is not ownership per se that is the problem, but rather the strategies that private equity firms employ (as Bos and Harrington (2017) point out). This is reflected in the fact that, generally, those studies that use staffing level as their dependent variable find that there is an effect of private equity ownership on care quality (e.g. Harrington et al., 2001, 2012; Pradhan et al., 2014), because they are directly measuring the use of a specific management strategy. By contrast, Huang and Bowblis (2019) (who do not find that private equity ownership has an effect on quality) use staffing levels as a control variable, meaning that they are effectively controlling-out one of the main mechanisms through which quality of care might be reduced by private equity firms[14]. In order to develop a more nuanced picture of the impact of private equity ownership on quality of care, we must embed our understanding of the specific strategies undertaken by private equity firms—and their dynamics linkages with other factors that might affect quality of care—into these statistical models.

This underlines the focus of our paper on specific financial engineering strategies and emphasises the need to now ask how each of these strategies is related to quality of care. For example, is a higher debt-to-equity ratio associated with lower quality care? Do companies with owners in offshore tax havens have lower quality care than those with UK-registered owners? Are higher financial costs associated with lower wage growth and reduced investment in physical infrastructure? How do factors such as preference shares, complex management hierarchies, and intra-group loans affect the ability of owners to extract cash from the operating business? A research agenda focused on the impacts of specific and combined financial engineering strategies would open up a raft of potential questions. However, building this research base is particularly challenging due to the “lack of public information about ownership, costs and quality of services” in many countries (Harrington et al., 2017, p. 1). The gap in research looking at these issues is particularly notable in the UK given the prevalence of private equity ownership here and given the depth and breadth of the multiple ongoing crises in the sector.

5. Discussion and conclusion

In this paper we have described the structures of marketisation and financialisation in the UK’s adult social care sector. We have argued that the social care sector is poorly suited to being operated as a market for four core reasons: limited scope for labour productivity growth; the power of local authorities to set prices unsustainably low; lack of consumer access to information about price; and the inability of consumers to express their preferences between providers. We have also presented primary data detailing the financial engineering strategies employed by the five largest private care home chains in the UK, demonstrating that all five chains exhibit some form of engineering. In particular, we focus on the presence of debt-leveraged buyouts, intra-group loans, the use of offshore tax havens, and sale and leaseback arrangements. Lastly, we explored the literature looking at the relationship between private equity ownership and quality of care, arguing that there is a need to develop the evidence base around the impacts of specific private equity management strategies on quality of care. Below, we reflect on this work from a political economy perspective, discussing how specific market structures and financial practices create a fragile, crisis-prone social care sector.

Through a political economy lens, we argue that the use of financial engineering tactics appears to amount to a concerted effort by financialised firms to shift the costs, socialise the risks, and privatise the benefits associated with investing in care. First, we contend that the costs associated with the financialised model of social care provision (e.g. interest payments, management fees, high rents, etc.) are shifted from investors onto workers and service users through cuts to services, low wages, and poor working conditions (Burns, Hyde and Killett, 2016; Horton, 2019). This highlights how the market power of care providers over consumers, combined with a general societal undervaluing of care work (Horton, 2017; Bunting, 2020), can act as a source of value to investors. Costs are further shifted onto the state through the institutionalisation of a 12% expected return on investment in the ‘fair price’ asked for publicly funded beds (Burns et al., 2016).

Next, the financial and legal risks associated with investing in care homes are largely socialised. This happens in two ways: one, the Care Act (2014) explicitly leaves the ultimate responsibility for continuity of care in the hands of the local authority when a provider can no long carry out its duties. Two, the use of holding companies can insulate investors from some financial and legal risks if a subsidiary becomes insolvent or causes harm (Muchlinski, 2010). All this means that cleverly structured companies can avoid (i.e. ‘shift’) all but a small proportion of the losses and damages associated with poor quality care and home closures.

Lastly, the benefits of investing in adult social care are captured by a small number of individuals. In Section 3 we explored how financial engineering tactics strive to maximise returns for investors and simultaneously reduce tax obligations. In addition to this, active lobbying by financialised care providers for government to funnel more money into the sector props up a comfortable margin for shareholders (e.g. The Care Collapse report, co-published by Four Seasons and HC-One, among others (Crawford and Read, 2015)).

The consequence of these strategies is the creation of conditions of financial and operational fragility across a significant portion of the UK adult social care sector. Specifically, we argue that some of the tactics used to increase rate of return for investors—e.g. LBOs and asset stripping—have the potential to leave the core operating businesses financially vulnerable, at increased risk of insolvency. This is, in part, because they end up with “only a small buffer to deal with any changes in financial flows” and are therefore “highly vulnerable to downturns in occupancy or fee rates” (Bayliss and Gideon, 2020, p. 35). Reflecting this, the CQC has had to exercise its market oversight function[15] twice since 2018; something that it takes as “an indicator of increasing fragility in the market” (Bayliss and Gideon, 2020, p. 35).

As well as undermining the long-term economic viability of social care companies, we find that the diversion of funds away from investments in frontline service provision, and towards rapid extraction of cash out of the operating business, may create operational fragility[16]. We can already see the indicators of this in the high prevalence of intra-group loans, management fees, exorbitant rents, and preference shares among financialised providers (Kotecha, 2019). These sit amid other arguably extraordinary costs which, as discussed in Section 3 above, appear to be used in some cases to extract rents for offshore owners. Media reports linking the collapse of Southern Cross in 2011, and the movement of Four Seasons Health Care into administration in 2019, to their high debt and rental burdens are certainly consistent with our hypotheses[17]. These examples offer a warning about what can happen when financial engineering goes badly wrong, with Southern Cross employees reporting that “the company had cut spending on the physical environment, to the extent that several homes that had been “run down to rack and ruin”, were shut by the regulator, and their residents forced to relocate” (Horton, 2020, p. 8). As stated by Burns et al. (2016, p32) “altogether, this looks like moral hazard through financial engineering, because those who create the internal conditions of fragility and crisis are not those who have to pay for it”.

The architecture of this system creates an ongoing need for revenue growth, in order that providers can meet the exceptional demands of a heavily financialised corporate structure. Ultimately this implies ever-increasing funding from government, thereby also creating a strong dependence on growth in the wider economy (Jackson, 2020). In a broader context in which economic growth is either infeasible or undesirable (Jackson, 2019) and in which social care is already desperately underfunded, and unmet need is continuing to grow, it is very difficult to justify the use of public funding for these ends. As Bayliss and Gideon (2020, p. 36) highlight, this also has “major implications for transparency and accountability”. In short, there is a risk that public money is being paid to companies who have the architecture in place to move profits to offshore tax havens, and to reduce their UK tax bill in the process. Given the depth of the ongoing financial and social crises in social care, there is a pressing need for the government to get a better grip on the scale of these accountability issues, and to take action where necessary.

Questions about the accountability and transparency of privatised, financialised welfare services have broader implications than adult social care. Children’s social care (Rome, 2020), healthcare (Bayliss, 2016), and social housing (Monbiot et al., 2019) are all grappling with related issues of financialisation and growth, distribution of ownership, and quality of service provision. These issues are also pertinent for social care systems in other countries, as industry reports suggest that private equity involvement in health and social care is continuing to grow across Europe and North America (Bain & Company, 2020; Klingan and Podpolny, 2020).

It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss alternatives to the current marketised and financialised structure of adult social care. However, our paper provides a holistic analysis of the dynamics driving many of the challenges identified in the media, analysed by academics, and lived by those in the sector. In particular, we use a political economy lens to identify how the economic and financial structures of social care combine to create dysfunctional outcomes, such as economic and operational fragility, low wages, unmet need, and hidden subsidies. Our recovery from Covid-19 now presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to transform adult social care. This paper demonstrates that fixing these dysfunctional market structures and financial practices must be a priority: urgent radical transformation is needed.

[1] Here we refer specifically to residential homes (those providing basic care services), nursing homes (providing more advanced nursing services) and domiciliary care services (those providing care services in the home) for the elderly.

[2] This is the legal minimum pay for over 25s; care workers aged 18-24 may be paid less.

[3] Outbreaks reporting style changed after that point and was no longer centrally collated.

[4] Throughout this paper we use the term ‘consumer’ to identify the individuals using or consuming the purchased goods, not the ones purchasing them. Hence it is used interchangeably with the term ‘service user’.

[5] This figure is arrived at by telephone survey—conducted annually by Healthcare consultancy LaingBuisson—and represents the normalised expected return in the sector (Laing, 2008).

[6] These might be a mix of “public and corporate pension funds, insurance companies, endowments and foundations, sovereign wealth funds, and wealthy families/individuals” (Rosenbaum and Pearl, 2009, p. 163)

[7] The loan package usually includes a number of tranches of debt, from “senior and secured” debt, which takes repayment priority, to subordinated mezzanine debt that is typically unsecured (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2009).

[8] Note that LBOs will still increase returns on equity (compared to pure equity financing), even if none of the debt is repaid over the investment horizon. This is because the initial equity input from investors is less, so any returns generated when the company is sold will represent a greater proportion of that initial investment.

[9] The management structure of HC-One and its parent undertakings is far too complex to represent in a diagram that is still readable. Hence, in Figure 3 we have opted to show a small fraction of the relationships between the group subsidiaries, with the intention of effectively illustrating the particular mechanisms of interest.

[10] https://privatefunddata.com/private-funds/fc-skyfall-lp/

[11] Accounts found in the consolidated financial statements of Care UK Health & Social Care Holdings Limited

[12] https://opencorporates.com/companies/pa/155585007; https://opencorporates.com/companies/lu/B155153

[13] This is a collection of care services whose accounts are found in the consolidated financial statements of The British United Provident Association Limited

[14] The exception to this is Stevenson and Grabowski (2008), who found no effect despite using staffing as an outcome variable. However, according to the paper, the majority of the private equity transactions in their dataset were very recent, limiting their ability to detect their effects.

[15] Under which it can report large, financially unstable social care companies to the local authority to aid contingency planning.

[16] Any strategies that (unwittingly or otherwise) undermine operational stability in this way are likely to be counterbalanced to some degree by the investors’ need to demonstrate long-term viability when the time comes to sell the social care company at the end of the investment horizon.

[17] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/apr/30/four-seasons-care-home-operator-on-brink-of-administration; https://www.ft.com/content/0a4d2570-e4f7-11e9-9743-db5a370481bc; https://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/jun/01/rise-and-fall-of-southern-cross

The full paper is available for download in pdf (8 MB). | Corlet Walker C, Druckman A and T Jackson 2021. Careless finance: Operational and economic fragility in adult social care. CUSP Working Paper No 26. Guildford: Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the ESRC South East Network for Social Sciences. It also forms part of the interdisciplinary research programme at the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (ESRC grant no: ES/M010163/1). We would like to thank Nick Taylor, Stephen Allan, Amy Horton, Sue Venn, Alison Armstrong, and Madeleine Bunting for many fruitful discussions. We would also like to extend particular thanks to Ann Gallagher, Gillian Orrow, Shakti Kumpavat and Rosalie Warnock for their insightful review and comments on the paper.