Why do we still worship at the altar of economic growth?

Forty years ago, Fred Hirsch pointed to a crucial flaw in the emphasis on growth as a central objective in western economies. His seminal book made the case that in addition to ecological limits, there are important social constraints at play. In this blog, his son Prof Donald Hirsch is arguing that these limitations became ever more relevant today.

After a decade of tepid economic performance, we still regard Britain’s headline growth rate as a beacon of our national fortunes. Those looking for signs of an impending economic car crash resulting from Brexit feel provisionally vindicated by the IMF’s recent downgrading of the UK forecast growth rate to below that of Greece. Yet the continued emphasis on growth as the central national economic objective flies in the face of three things we should have learned over the past 40 years. First, it doesn’t necessarily “trickle down”. Second, indefinite expansion of global output, as presently defined, may be unsustainable. And third, increases in monetised economic activity do not automatically increase overall well-being.

Forty years ago this year, my father Fred Hirsch pointed to a crucial flaw in the emphasis on growth as a central objective in western economies. His seminal book, Social Limits to Growth, argued that once a nation is able to provide basic essentials such as food, clothing and shelter for its citizens, further growth increasingly acquires a social element in the sense that one person’s consumption can affect that of others. In particular, there is a growing emphasis on “positional goods” whose overall value is finite because one person’s consumption can reduce their value to other consumers. This can be because their value derives from status (the shiniest car on the block) or relative position (the educational qualification that will get you a top job) or because value is diminished by crowding (access to an empty beach).

In the 1970s, a waning belief in Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” (the idea that everybody will benefit economically from individuals acting selfishly) had made redistribution fashionable. But Fred Hirsch pointed out that even redistributed growth would face these social limits if the paradigm remained individual spending in pursuit of personal well-being, as it favours competition over co-operative forms of consumption and collaborative behaviours.

Since that time, thoughtful economists have increasingly sought alternative measures of well-being that do not just rest on individual consumption, but have not yet managed to knock conventional GDP off its pedestal.

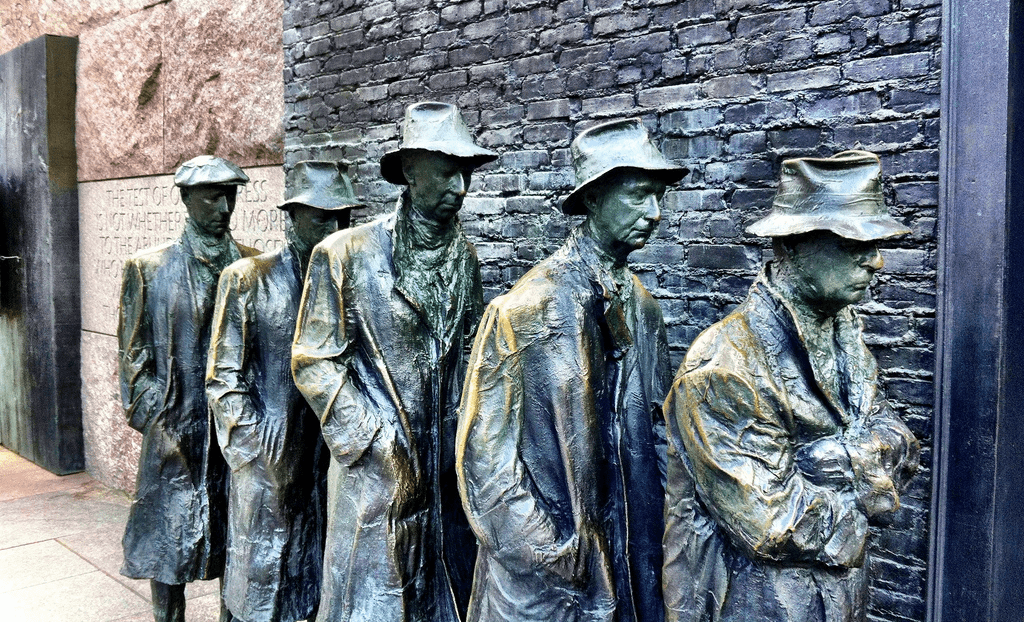

But two fundamentals have changed to make it more clear-cut than ever that growth on its own is insufficient as an economic ideal. First, as Thomas Piketty has shown, the 1970s were the high-point of economic equality, since when the distribution of wealth and income has become far more unequal, with the rich appropriating most of the growth that has occurred within each country, especially in the United States. As well as drawing the automatic social benefit of growth into question, widening inequalities vastly increase the importance of positional goods, since the stakes of where you are located in the pecking order (such as whether you have the qualifications to access one of the best 10% of jobs) increase greatly when outcomes are so unequal. Writers such as U.S. economist Robert Frank have drawn attention to a consumers’ “arms race” or “luxury fever”, in which a huge share of national resources is used by richer individuals to stay ahead in consuming goods of every-increasing material value.

The second fundamental change is that a socially fruitless pursuit of positional advantage, particularly by the rich, has become especially problematic because of the need to contain some aspects of global consumption, notably those that increase carbon emissions, reduce biodiversity or otherwise pollute the planet. The original “social limits” thesis in the 1970s was a reaction to a physical “limits to growth” argument based on the idea that the world’s oil would eventually run out: Fred Hirsch was pointing out that already-present social limits to growth are much more pertinent than apocalyptic projections of the material conditions of the future. Today, however, strategies to address physical constraints have become central, such as through the target to reduce Britain’s carbon emissions by 80% between 1990s and 2050. They interact with social limits by making vital aspects of consumption a “zero-sum game” in which one person’s gain necessitates another’s loss.

Such constraints have the potential to create intense political tensions. My own research at Loughborough University shows that three in ten households today have incomes below the level that they would need to afford a decent minimum standard of living as defined by the general public. Yet it has been estimated that even if everybody in Britain lived exactly at this minimum level (ie not only making the 30% below it richer, but the 70% above it poorer), greenhouse gas emissions would fall only by 37% not the 80% needed.

The clear conclusion is that in a world where we are trying to contain overall material consumption, there is a strong case for curbing the excesses of the rich in order to improve living standards at the bottom, but that this on its own cannot be enough.

Smart consumption may provide some of the answer: technologies that allow us to consume more without overtaxing the planet. But they are unlikely to be enough to allow us to reach the living standards we expect, especially if we continue to ignore the fruitless social results of competitive consumption. Here there is an encouraging convergence between what my father was suggesting forty years ago and the ideas of thinkers such as Tim Jackson, author of the pioneering book Prosperity without Growth. The latter argues that we need to redefine what makes us well off, putting far greater emphasis on social collaboration. Back in 1977, Fred Hirsch had pointed out that “the only way to avoid the competition in frustration is for the people concerned to coordinate their objectives in some explicit way”. He suggested that while religion’s power to steer moral behaviour has declined, even if people behave as if they were altruistic, everybody can become better off from the shared benefit. Today, technology offers new routes to “collaborative consumption”, although the idea that a “sharing economy” could replace individualism with mutuality is hotly contested.

It would be easy to be gloomy about how in an increasingly unequal society, our economic efforts are being channelled more than ever into generating fruitless, competitive consumption. This can be countered not just by a new redistributive impulse – so far articulated most powerfully through rhetorical attacks on the rich in the wake of the banking crisis – but also by reminding ourselves that the sum of individual spending or consumption is not the only way to measure or promote economic success. If we are on the verge of a break with the neoliberalism that has dominated the past few decades, we need to get beyond thinking merely about how our economic fruits are distributed and also think about what it is that we truly value.