In the Age of Extinction, Who is Extreme?—A Response to Policy Exchange’s “Extremism Rebellion” report

In July 2019, the think-tank Policy Exchange put out a report that frames the Extinction Rebellion in terms of extremism with potential to terrorism, calling on government for forceful approaches to curb the XR movement. A worrying assessment that is far from being justified, Simon Mair and Julia Steinberger write in their defence of XR’s economic and political programme: Given the outlook of climate breakdown, what constitutes extremism, and who gets to decide this? (This comment first appeared on OpenDemocracy, 23 July 2019).

There is a spectre haunting Europe, the spectre of… environmentalism?

There is overwhelming scientific evidence that we are living in a time when radical, rapid and far-reaching changes are needed to avert environmental disaster. Scientific evidence supports Extinction Rebellion’s statement that “Humanity finds itself embroiled in an event unprecedented in its history. One which, unless immediately addressed, will catapult us further into the destruction of all we hold dear…”

Given such an extreme future, what constitutes extremism, and who gets to decide this? On the 16th of July the right-wing think tank Policy Exchange put out a report claiming that Extinction Rebellion are an extremist organisation. The report attempted to link Extinction Rebellion to terrorism. Among the more worrying recommendations were calls for a more forceful approach to prosecuting non-violent protestors, even changing the law to give police radical powers to shut down peaceful protest. Where do these views come from, do they have a basis in fact, and what purpose do they serve?

To answer this, we consider three accusations of extremism made by the Policy Exchange authors against Extinction Rebellion: (1) it is anti-democratic; (2) it is anticapitalist and anti-growth; (3) its potential for violence deserves extreme repression. In each case we argue that the weight of evidence supports the idea that Extinction Rebellion’s program is coherent and necessary.

The case for reforming democracy

To manage ecological crises, there is a need to remedy anti-democratic deficiencies within our political systems. The scientific basis of climate change and ecological breakdown has been established for decades. Yet we hurtle onward towards disaster. Fossil fuel use and biodiversity loss are not only still rising: they are accelerating. Our existing governments and market institutions have not responded to the challenges of climate breakdown and ecological crises. They must be changed.

A key source of anti-democratic deficiency is the corrupting influence of the climate denial industry. The most brazen examples are outright climate denial campaigns. Funded by large companies (led by the fossil fuel industry, but including others like Google and Amazon) through complex networks of think tanks and lobby groups, these campaigns span multiple decades and directly attempt to undermine the scientific basis of climate change. Having mostly lost on this front, they have now moved on to simply delaying action using all means possible. But there are also more pernicious mechanisms at work, such as when fossil fuel dependent sectors of the economy threaten to withdraw or relocate in response to limits on emissions.

Our current, democratic systems have not been up to the task of countering this corruption. This is hardly surprising: representative democracies were often specifically designed to tilt the scales in favour of existing economic power, rather than the needs of the majority of the population.

Extinction Rebellion’s proposed reforms of existing democratic institutions are in line with the latest academic findings and practical action in this area. Among others, political theorist Dr Marit Hammond has convincingly argued that our current democratic structures are insufficient and that more direct democracy is needed to combat the ecological crisis. Specifically, Extinction Rebellion are calling for Citizen Assemblies to deliberate on the best way forward on environmental crises. Citizen Assemblies are not far-fetched or extreme structures, they exist in many countries, including most prominently Ireland, whose Citizen Assemblies’ work on abortion rights and climate has won international praise.

The case for reforming the economy

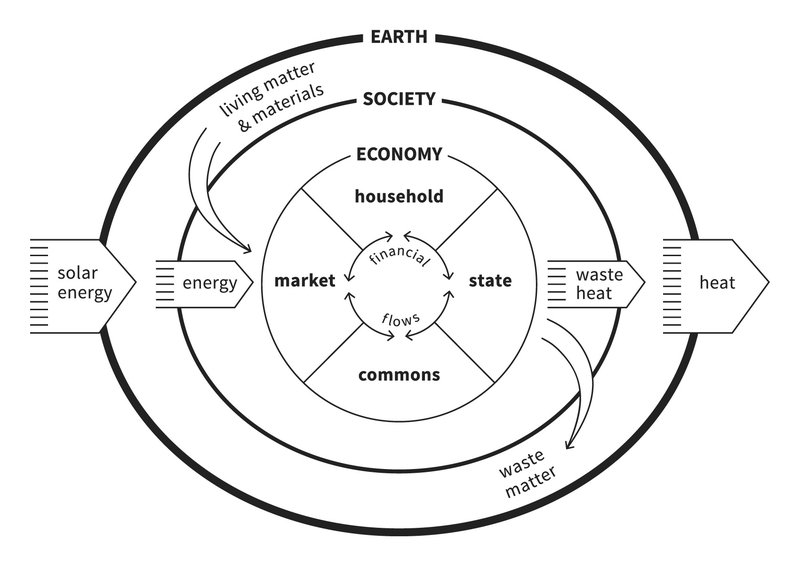

Researchers (including ourselves!) have long studied the connection between economic growth and the environment. The ‘degrowth’ or ‘post-growth’ position is that a growing economy makes reducing environmental impacts harder at best, and impossible at worst. The core argument is that all economic activity is based on the use of energy to transform materials. This is illustrated in Kate Raworths ‘embedded economy’ diagram. The economy takes in energy and materials from the environment and emits wastes and pollution to the environment.

When we investigate the material and energy basis of the economy, the empirical evidence shows that we must either reduce the size of the economy, or become much more efficient – using less energy and materials to make ever more stuff. We have no evidence that we are able to become efficient enough to reduce overall environmental impact whilst still growing the economy. Tim Jackson explains that to decarbonise while growing the economy, we would need to do so at a rate 50 times faster than we managed in the last decade. In short, ‘green growth’ requires the invention of miracle technology. Given the immediate and urgent risks we face, waiting for a miracle seems to us to be the more extreme position.

These are the reasons that the post-growth view is far from fringe. Kate Raworth’s growth-agnostic book ‘Doughnut Economics’, was a Sunday Times bestseller. Tim Jackson’s TED talk “Prosperity Without Growth” has over 1 million views. In the UK, there is a parliamentary group on the limits to growth made up of members from all major political parties. These are not the views of fringe extremists.

Some post-growthers (ourselves included!) also criticise capitalism, since the profit motive and competition at the heart of capitalism inexorably lead to expansion, social exploitation and environmental degradation. This position, just like the more general post-growth one, is far from extreme. To give a couple of examples: Ben & Jerry’s ice cream company recently tweeted “Capitalism may be great for selling ice cream, but it’s not great for saving the earth.” Even in the USA, recent survey data found that more Democrats prefer socialism to capitalism, with most young Democrats having a negative view of capitalism.

In short, there is a large body of evidence supporting the idea that growth makes meeting environmental targets much harder than it need be. Many academics working in this area argue that profound economic reform is not extreme: it is necessary.

Do Extinction Rebellion’s tactics deserve extreme repression?

We have set out our reasons for believing Extinction Rebellion’s demands and program for reform to be reasonable: ecological breakdown is an unprecedented threat to civilisation. Critiques of growth, capitalism and our current, limited, forms of democracy are necessary to combat this threat. We have not yet tackled the most worrying and unfounded demands of the Policy Exchange report: the smear that Extinction Rebellion are terrorists, and that the state must step in and crackdown on their peaceful protests.

This accusation is baseless. It rests on the pure speculation that “some on the fringes of the movement might at some point break with organisational discipline and engage in violence”. It is unfair to smear an entire social movement, and hundreds of thousands of dedicated sympathizers, on the basis of something that has not happened. It is troubling that Policy Exchange would use such baseless smears to advocate state repression of peaceful protest.

The Policy Exchange authors are claiming that any challenge to our current institutions of parliamentary democracy and capitalist profit-driven economies is extreme and deserves repression. The implication is that anyone who criticizes the structure of our polity and economy should be considered an extremist. Under such a view, almost all social movements are ‘extreme’. Both the suffragette and the civil rights movements critiqued democratic and economic institutions. Emmeline Pankhurst openly declared “We are here, not because we are law-breakers; we are here in our efforts to become law-makers.” Similarly, Martin Luther King Jr. stated, “One has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.” Were they unreasonable extremists? Or rather are the conservative authors of the Policy Exchange report trying to place extreme limits on democratic dissent?

Conclusion: who is served by which side of this debate?

The real concerns of the Policy Exchange report authors are demonstrated through their call for the state to step in and protect ‘our free-market economy’. The defining characteristic of neoliberalism is the use of the state to create and protect markets. Since Adam Smith, economists have known that markets represent the interests of the rich. Moreover, Policy Exchange’s lack of transparency regarding its funders, the notable absence of support for any form of robust or effective action on climate breakdown and its approving quote of an unelected climate denying coal baron, provide us with some hints as to which specific market interests and industries they may be protecting.

In contrast, in organising to protect the biosphere, Extinction Rebellion are working to protect all of us. We cannot live on a dead planet. We must do all we can to protect the basic environmental conditions that allow humanity to flourish. In this context, Extinction Rebellion’s economic and political program is on the side of reason, and well supported by academic research.