*EMOTIONAL* MONTAGES and the comfort of meritocracy

Since the first lockdown, CUSP researcher Mark Ball’s cultural engagement has almost always been through a screen, and mainly his laptop screen. Here are some reflections on one regular avenue for comfort and now concern: montages of talent show success on YouTube.

Anyone who has watched Britain’s Got Talent (or similar) at the audition stages will be familiar with the change in tone at the end of the episode. The music shifts to some soft piano and the whole pace drops, and the hero of the show is presented. Having enjoyed some of the funny, sometimes charming and sometimes laughable performances, this is the final act.

The cutaway interviews are longer. Hardships and adversities are described—the stories change each week but the flavours are similar. Quickly they aren’t a stranger, the viewer now knowing something intimate enough to make them a friend. They are treated to an extra few seconds on stage before the performance starts. Maybe they won’t be any good?

Then the first big note, or dance move, and the camera cuts to a crowd of shocked expressions. At home it’s not really a shock—it’s the last act so it will obviously be good, the Susan Boyle slot—but it’s nice to indulge in the shock of it all. These segments are perfectly crafted: in and out in 10 minutes, finished with praise heaped on the performer, sealing in the warm feelings.

Yes it’s transparent and highly telegraphed, but that’s also the point. Feeling a sense of pride in something or someone can be nice, and it’s nice to know it’s a guarantee when tuning in. I am almost always seduced by the romance of meritocracy—that yes, the cream will rise to the top, how lovely.

The Montage

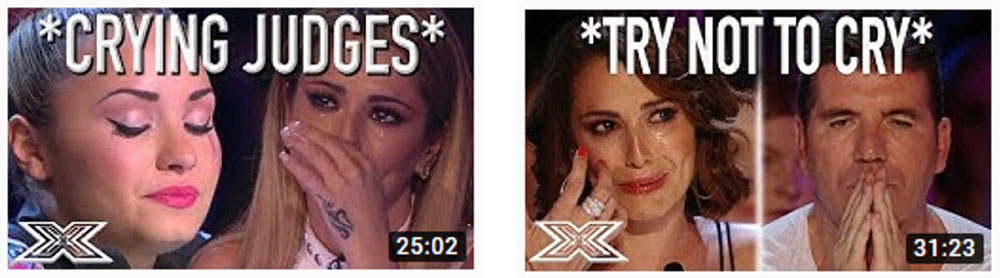

YouTube is now filled with collections of these 10-minute emotional hit pieces, and during lockdown I have been properly algorithm-ed by them. Rather than sitting through the first 40 minutes or so of preamble, now you can cut straight to the best bits over and over again. With titles like “MOST EMOTIONAL AUDITIONS EVER!” and “SUPER EMOTIONAL Auditions Have Judges in TEARS! *CRYING JUDGES*”, they advertise their affects and they have millions of views. Rather than the (relatively) steady, managed ramping-up of emotional pitch the hour-long shows deliver, here emotions are always on the boil.

YouTube has mainstreamed montages. There is maybe something more to be said about montage-ification (sorry), but I have just been consuming these *emotional montages*. Though Cowell-esque shows are on the decline in the UK, these *emotional montages* seem not to be.

To watch a whole series of X Factor or The Voice means losing something from the perfect moment. The origin story has been told and the zero-to-hero shock is gone—all that is left is to pick favourites and ride the series out. But YouTube gives access again and again to these perfect moments, and indeed stack a series of perfect moments on top of each other.

Stacking these perfect moments crystallises an emotional quality only achieved by the montage. It doesn’t matter what happens to the performers the week after the audition, or in their lives when the show is done. They are a version of a perfect moment that doesn’t need an ending.

Comfort and cruel optimism

I don’t understand why I have an obsession with making myself cry…-.- arrgh!

W H O I S C U T T I N G O N I O N S ?!!!

When im angry I see this vid And i cry and after im in peace

—A selection from the comment section

Maybe us viewers of these montages lead terrifically empty lives. Or maybe these little trips to perfect moments help to live in at once turbulent and numbing times—where meaning doesn’t come easy. Mark Banks recently wrote that: “people in lockdown have turned to culture for some much-needed release, or for compensation and comfort. Any future value we attach to culture might well be influenced by a just appreciation that, in the time of national crisis, culture provided. But there is a danger here, also. Culture and art may well provide a good distraction from pandemic, but that is not their only purpose”. I have found these montages oddly comforting and distracting, but I agree there is a danger in seeing culture as usefully comforting and distracting.

This is all perhaps an example of cruel optimism—what Lauren Berlant describes when what we desire is also what collectively holds us back. Someone making it through a difficult time to find success makes for a nice story with a nice arc—Billy Elliot is a feel-good film, or at least packaged as one.

But lots of people don’t come through hard times to find success and most people on X Factor don’t turn into One Direction. One of the problems with meritocracy, if considered problematic, is that it can also be so comforting. I think, perhaps having watched too many of these montages, that this comfort isn’t a good thing—meritocracy is comforting because it’s always presented as comforting, wrapped up here in all the talent show shtick, and now re-wrapped through montages. Inevitability it seems, these are the best stories to tell because they are the stories that get told: individual triumph over adversity, rather than collective effort to tackle those adversities. To reject the optimism of these perfect moments is difficult because it means rejecting a sense of meritocratic meaning.

Maybe there is space for “*GREATEST MOMENTS OF SOLIDARITY OF ALL TIME!!*” or “Super EMOTIONAL!! COLLECTIVE ETHOS GUARANTEED!!”. But maybe as well these kinds of ideas and sentiments don’t work in short bursts. It would be nice though to find comfort elsewhere.