Held to Ransom: What happens when investment firms take over UK care homes

Christine Corlet Walker, Vivek Kotecha, Angela Druckman and Tim Jackson

CUSP Working Paper Series | No 35

Summary

The involvement of investment firms in the UK’s adult social care sector is a cause of mounting concern. Many of the strategies that investment firms use to achieve returns for their investors expose whole chains of care homes to large costs and increase the risk of bankruptcy and closure. This ‘financialisation’ of care has been implicated in the high-profile collapse of several large care home chains. However, little research has been done looking at the direct impact of these strategies on workers and service users in the care homes themselves.

In this report, we present the findings from a series of interviews with care workers who were working in care homes during, or shortly after, they had been taken over by an investment firm. Our respondents expressed five key concerns about the behaviour of their new employers. Specifically, they felt that their care companies were:

- exploiting care staff;

- cutting corners on service delivery;

- covering up mismanagement;

- failing to communicate; and

- prioritising profit over care.

We also studied the financial accounts of fifteen of the largest care home chains in the UK and uncovered a large and widening disparity between the pay of directors and the wages of employees. This pay gap was growing particularly fast in investment-firm-owned chains. The pay ratios between the highest paid director and the average employee within the care companies in our sample were similar to those ratios found in large for-profit companies in other sectors, but far higher than those found in public services like the UK’s National Health Service. This disparity existed even for some not-for-profit groups.

Our analysis paints a picture of a sector that is deeply unfair, not only in terms of who benefits from the financialisation of care, but also in terms of who pays the price. We contend that achieving a care sector that works for workers and service users rather than investors and profiteers means removing the profit motive altogether, reducing the size and complexity of care home groups, and strengthening care workers’ rights and voice in the workplace.

1 Introduction

The UK’s adult social care sector has for a decade or more been in a state of crisis (Bunting, 2020; Dowling, 2021). A long history of under-valuing care work has combined with policies of austerity to starve the system of adequate funding and create the conditions for endemic low pay for care workers. This backdrop has then been exacerbated by Brexit and Covid-19, creating catastrophic workforce shortages (more than 105,000 vacancies were reported by Skills for Care in 2020/21 (Fenton et al., 2021)). On access to care, Age UK estimates that there are around 1.5 million older adults with some level of unmet need (Age UK, 2019); this number likely grows if we include missing care for younger adults with physical and mental health needs and learning disabilities, although estimates for these groups are difficult to come by (Forrester-jones and Hammond, 2020).

Despite this precarious position, around 10% of revenue is leaking out of the sector each year in the form of directors’ fees, shareholder dividends, interest and rental payments (Kotecha, 2019). This leakage is, in large part, due to the financialisation of care. Over the last 30 years, the adult social care landscape has changed dramatically, with the number of publicly provided residential care beds falling by 88% from 1980 to 2018 (LaingBuisson, 2018). The private sector has absorbed the majority of these lost beds, accounting for around 84% of the market (by number of beds) by 2019 (Blakeley and Quilter-Pinner, 2019). Most notably, approximately 12% of care beds are now in the hands of investment firms, including private equity, hedge funds, and real-estate investment trusts (REIT), among others (CQC, 2022). Investment firms are drawn to the sector for similar reasons: an aging population with growing needs, asset rich care providers, and guaranteed government funding. However, they differ in the extent to which they are directly involved in running the care home services and the length of time that they intend to stay invested.

Many of the investment firms who have taken over adult social care services employ financial engineering tactics such as debt-leveraged buyouts, asset stripping, and the offshoring of profits (Corlet Walker, Druckman and Jackson, 2022). These strategies tend to be aimed at achieving one of three things: 1) extracting a one-off, large sum of money from the business; 2) extracting cash from the business on an ongoing basis; or 3) increasing the value of the business so as to secure a windfall when the business is sold on (Corlet Walker, Druckman and Jackson, 2021). The drawback of such approaches is that pursuing these goals can sometimes compromise other factors, such as quality of care (Gupta et al., 2021), economic and operational sustainability (e.g. debt-leveraged buyouts are associated with a higher risk of company insolvency (Ayash and Rastad, 2021)), transparency and accountability (Kotecha, 2019), value of money for the taxpayer, and/ or working conditions (Horton, 2019). The potential implications of these risks have been exemplified by the high-profile collapses of two of the UK’s largest providers—Southern Cross and Four Seasons Health Care—in the last decade or so.

In this report, we explore what the challenges associated with financialisation look like within the UK’s care sector. We analyse qualitative data that was gathered through interviews with care workers who worked in residential and nursing homes during, or shortly after, a change of ownership. We look specifically at residential and nursing care for adults over the age of 18—including care homes for individuals with learning disabilities or mental health needs, as well as elderly care—with a primary focus on care workers whose care homes were taken over by investment firms. Our exploratory, qualitative approach to this task reflects both the dearth of literature looking at these dynamics in a UK setting, as well as the lack of available quantitative data on clinical outcomes, care quality, staffing, working conditions and price. The remainder of this report is structured as follows: Section 2 will briefly review what we know so far about how investment firm ownership affects key outcomes in the care sector. Section 3 will outline our methodology for collecting and analysing our data. In Section 4, we present the results of our thematic analysis. Section 5 looks at pay disparities and key performance indicators in fifteen of the UK’s largest care home chains. Finally, in Section 6, we discuss how our analysis builds on the knowledge laid out in Section 2, and we offer a series of policy recommendations for the sector, moving forwards.

2 Background and project aims

There is a small but targeted body of literature that uses statistical approaches to investigate the impacts of financialisation on care. This research predominantly focuses on nursing homes in the United States, thanks to the rich quantitative data available there. For example, national reporting of nursing home deficiencies was first established in the US in 1998. Nursing home report cards now include a raft of indicators on clinical outcomes, staffing levels, and health or safety breaches, and are published on the national Nursing Home Compare website—a site managed by the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services (Tamara Konetzka, Yan and Werner, 2021). This is in contrast to the UK, which has a more limited range of data available for such analyses. The Care Quality Commission (CQC), established in 2009, publishes its inspection reports; however, these are largely categorical and descriptive in nature, and do not include systematic data on clinical outcomes.

Studies from the US report a mixed picture in terms of the impact of investment-firm ownership on outcomes in the nursing home sector. Some find that homes with private equity owners have lower levels of staff per resident, lower-skilled staff on average, and higher numbers of incidents of deficiencies, as compared to other firms (Harrington et al., 2001, 2012; Pradhan et al., 2014; Gupta et al., 2021). By contrast, others found no difference in quality (Stevenson and Grabowski, 2008; Huang and Bowblis, 2019). These studies differ in what factors they pay attention to, and which they omit. To our knowledge, the most comprehensive analysis to date has been conducted by Gupta et al. (2021). The paper finds substantial impacts, with a 10% increase in resident mortality associated with private equity ownership over the short-term.

A general limitation of these quantitative studies is that they are largely dependent on the scope of publicly available data sets and may therefore be missing or neglecting key pathways to impact. To better understand the full range and depth of the impacts of investment firm ownership, more exploratory approaches are necessary. In pursuit of this, Bos and Harrington (2017) used a single case study chain to ask: “what happens to a nursing home chain when private equity takes over?”. The authors combined a range of data sources, from interviews with investors, care company executives, and lawyers, to press releases, litigation reports, and indicators of financial performance and resident well-being, among other things. They found that the private equity owner used specific strategies, including low staffing levels, debt-leveraging, re-branding and corporate re-structuring (including separating the property and operating companies in what is known as an ‘op-co prop-co split’). This study highlighted the importance of considering which strategies might be responsible for generating poor outcomes, rather than focusing on ownership type per se.

Burns, Hyde and Killett (2016) was one of the first papers to take such an exploratory approach for the UK, using data from 12 case studies in the post financial crisis period to understand how job quality and care quality are related within nursing homes. Looking at the financial pressures on care organisations after 2008, the authors highlight that care companies at the time needed to manage budget deficits, leading management to “demand more of people at work, as organizations look[ed] to their workers to do more with less” (Burns, Hyde and Killett, 2016, p. 992). They found that the two private equity owned care homes were facing “intensified” financial pressures as a result of the specific financial engineering strategies used by the investors, resulting in “cutbacks in the catering, maintenance, and staffing budgets”. Staff in one of the homes reported that they regularly worked short-staffed, that managers were under pressure not to bring in agency staff and that there were often medication mistakes by nurses (Burns, Hyde and Killett, 2016, p. 1008).

Building on this work, Horton (2019) undertook a series of 25 interviews with investors, industry representatives, regulators, union officials and care workers in private equity owned homes in the UK. Horton (2019) found that, on top of lower wages than the industry average and prolonged pay freezes, care workers also reported that investment firms were reducing sick pay and overtime pay. Further, they reported cuts to activities programmes, and some even spoke of being unable to “obtain basic equipment” such as commodes or sanitary pads (Horton, 2019, p. 9). Through these interviews, the author begins to shed light on key dynamics within the sector, including: how the sense of responsibility of care workers acts as a “source of value” to investors; how investors’ strategies for increasing profitability impact on workers and residents on-the-ground; and how care workers ultimately “complicate efforts” to raise the level of profitability of the company by, for example, refusing to ration key care supplies (Horton, 2019, p. 11).

These papers have begun to reveal what happens within care homes when investment firms take over. However, the literature is still new, and the existing papers are understandably limited in their scope. We therefore aim to take a more comprehensive look at the issues raised in previous works, asking the core research question:

What happens to quality of care and working conditions in UK residential and nursing homes when investment firms take over?

This report builds on existing knowledge by focusing largely on the experiences of care home workers and managers (rather than other actors within the care ecosystem) when their care home is taken over by an investment home. We also include the experiences of those working with adults with mental health needs and learning disabilities, something not widely done before.

3 Methods

The study consists of two core parts detailed below; 1) a set of interviews with care workers; and 2) a review of the financial accounts of large care home providers. Ethical approval for part 1 of this study was granted by the University of Surrey ethics committee. We give a brief overview of the methods used below, with a full methods description detailed in the appendix.

3.1 Interviews with care home staff

We conducted sixteen semi-structured interviews with care staff who were working in residential and nursing home facilities during, or shortly after, a change of ownership, with a primary focus on those who were taken over by investment firms. Prospective participants responded to three recruitment emails sent to a list of members of UNISON (one of the UK’s largest unions) who work in the care sector. We did not tell these individuals that we were interested in investment-firm-owned care homes. This was to avoid eliciting negative rhetoric about the involvement of private equity in the care sector. We felt it was necessary to approach the interviews in this way, given the number of recent high-profile news items discussing the role of private equity in the sector in a negative light. All participants were debriefed following the interview about our interest in investment firm ownership.

Table 1 | Participant characteristics and ownership types (verified using Companies House financial accounts and official statements from the company owners)

Table 1 is an anonymised summary of our participant data. In total, we interviewed sixteen care workers, fourteen of whom were working in the care home at the time it changed hands, and twelve of whom were working in a home that was owned by an investment firm. Where it is of interest, in the write up of our themes we highlight differences/ similarities between the experiences of participants under different types of ownership.

We conducted semi-structured interviews online, which lasted approximately one hour each. Participants were asked a mix of open-ended questions about their experiences of changing ownership in their care home. The data were transcribed, anonymised, and analysed using thematic analysis. This analysis involved attaching detailed codes to each chunk of data, according to their meaning. These codes were then grouped into themes which represent patterns of shared meaning in the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Our findings do not tell us about the prevalence of the issues uncovered within the sector. However, what they do tell us is that the issues and dynamics highlighted exist, and they can offer us insights about what processes are driving poor outcomes in the sector.

3.2 Review of company accounts

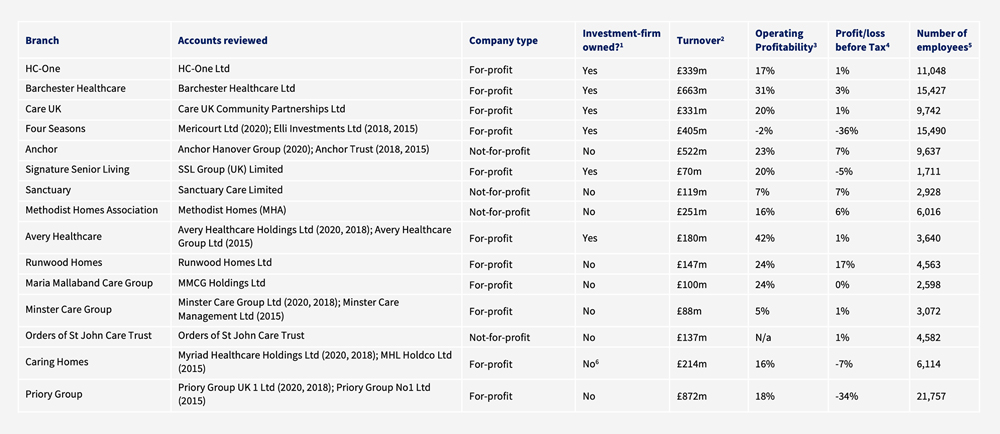

For the review of accounts, we looked at the key business metrics and key performance indicators (KPIs) of 15 of the largest adult social care groups in England, accounting for more than 90,000 care beds between them (approximately 20% of all care beds) by 2022 (CQC, 2022). See the appendix for an explanation of which firms were included and excluded from our analysis. Our final sample consisted of six for-profit groups that were owned by (or had a significant partnership with) an investment firm, five for-profit groups that were not owned by an investment firm, and four not-for-profit groups. See Table 2 for a summary of the companies included in our analysis.

We looked at accounts for the years ending 2015, 2018, and 2020. This allowed us to see changes over time along with differences between those care home groups owned by investment firms, and those which are not. Importantly, the analyses in Sections 4 and 5 were conducted separately and should be read as such. This means that the company accounts discussed in Section 5 will not necessarily correspond to the companies who employed the individuals we interviewed in Section 4.

When analysing the accounts, we focused on two core areas. First, we looked at core business metrics, such as differences in employee and director pay, staff costs, and profitability. This allows us to understand key aspects of business performance for each group.

Table 2 | Key financial information for fifteen of the largest adult social care companies in the UK, as at year end 2020

Second, we analysed key performance indicators. Due to their size, all of the companies studied are required, by law, to report financial and non-financial KPIs as part of their strategic report. The company directors choose which KPIs most effectively measure progress towards particular strategies or objectives, so that shareholders can understand the development, performance, or position of the business. They therefore provide an insight into which strategies and indicators matter most for a particular business.

4 Findings: Thematic analysis

Our thematic analysis of the interview data resulted in the development of the following five themes, which we elaborate in more detail in Sections 4.1 – 4.5 below:

- Exploiting care staff. The first theme we developed through our analysis details the various ways that our participants’ employers exploited them, from reducing staff benefits to chronically understaffing the care home. It also highlights the important role of staff in protecting residents from the negative impacts of this understaffing.

- Cutting corners on service delivery. The second theme builds on these insights, and goes into the range and depth of under-resourcing in the sector, beyond staff shortages. From stories of rationing medical and sanitary supplies and food, to neglecting care home maintenance and failing to deliver enriching activities for residents, interviewees painted a calamitous picture of a care sector that had been stripped back to the bare bones.

- Covering up mismanagement. Our third theme reflects participants’ views that their employer was often mismanaging their care home, and that, in some instances, they were trying to conceal the problems caused by that mismanagement from the industry regulator (e.g., by falsifying paperwork or putting more staff on shift during an inspection).

- Failing to communicate. This perceived mismanagement was compounded by a failure of internal communications—leading to our fourth theme. Interviewees expressed their frustration at the lack of open and effective channels for communication with their employer. They explained how this left them feeling ignored and in the dark about their future and the future of the care home.

- Prioritising profit over care. Finally, we heard from many of our interviewees that they felt their employer was primarily involved in the care sector to make money, and that they didn’t care about the wellbeing of staff or residents. This theme ties together the experiences across the four other themes, revealing interviewees’ perceptions about the motivations behind their employer’s actions.

The themes largely capture care workers’ experiences of how ownership and management decisions impact care services on the ground. Although most of our participants worked in homes owned by investment firms, there were some who did not, or who could compare to other types of ownership before the investment firm took over. Where pertinent we make clear that this is the case. Readers should also bear in mind the self-selecting nature of the study and the pool of participants. Both increase the likelihood that we are capturing more negative experiences than positive. Nonetheless they give us vital insight into what can happen when ownership goes wrong and why.

4.1 Exploiting care staff—“It’s almost like an unspoken ransom”

The accounts of study participants reported in this theme create a picture of care worker exploitation, and appear to represent a systematic attempt by employers to squeeze as much as possible out of each care worker, for as little money as possible. Sometimes care workers said this explicitly themselves, but other times, they simply conveyed the different ways in which the company limited how much they were spending on staff or pressured staff to take on more work, from reducing staff benefits (Section 4.1.1) to chronic understaffing of the care home (Section 4.1.2). Participants also detailed their attempts to protect residents from the negative impacts of these problems (Section 4.1.3). This theme was raised the most frequently by our interviewees, with all sixteen participants contributing to it.

4.1.1 Reducing staffing costs

A starting point for many of our respondents was the fact that staff in the sector feel undervalued and poorly paid. As Emily, a support worker in a care home for adults with mental health needs, put it:

“I think we’re massively undervalued. Massively undervalued. Unappreciated. That’s how we feel. We feel unappreciated.”—Emily

This was raised as a problem for the whole care sector and was sometimes linked to how much local authorities were paying per bed, rather than being an issue that was specific to a particular participant’s employer.

However, building on this baseline of poor hourly pay, many of the interviewed care workers reported that their employers used a variety of tactics to reduce staff benefits. These included limiting or not paying overtime pay, not paying staff for their breaks, limiting holiday entitlements (e.g., by expressing holidays in hours instead of days), reducing staff perks, and limiting pay progression.

The care workers we interviewed often contextualised the inadequacy of their pay and non-wage benefits by contrasting it with the high degree of difficulty and responsibility associated with the job. This was particularly the case for those working in care homes for adults with mental health needs or learning disabilities. For example, Emily spoke about some of the challenging situations she is placed in as a support worker in a mental health facility:

“When someone is in a crisis… if they want to kick your head in and do serious harm, they will. There are a few times we’ve had to dodge the microwave and other things getting thrown. Oh yeah, it has been quite hairy at times.”—Emily

She later went on to say:

“I love my job. Where I work, I absolutely love my job, but I don’t love the pay. I think the pay is horrendous for what they’re expecting me to do and for some of the situations we get put in. I think it’s disgusting.”—Emily

This feeling of disparity between the challenging nature of the job and the limited financial reward was echoed by Robert, a support worker for adults with learning disabilities, who commented:

“Yeah, I mean, like if the wage doesn’t meet the stress that you experience on a day-to-day basis, it’s not worth the job, you know what I mean. Like it’s not hard logic to follow.”—Robert

Beyond the often physically challenging nature of the job, some emphasised the legal and personal risks taken on by many care workers, in the form of administering drugs and completing medical paperwork.

“You go to prison if you give them meds out wrong.”—Will

4.1.2 Chronic understaffing of the care home

Understaffing was another issue that was raised repeatedly by all participants in our sample, with several arguing that the understaffing was an explicit choice by their employer.

“They’re not actually interested in the staffing levels because they say it’s adequate for the amount of residents; that was policy at the heart.”—Michael

Care assistant Laura said that management had repeatedly told staff over the course of her three years at the company that “no matter how many staff we get we’re still going to be understaffed, and that we just have to work smarter rather than harder”. It is difficult to be sure exactly what was meant by this (seemingly illogical) statement without speaking directly to the manager in question, but it could be read as a pragmatic resignation on the part of the manager to the fact that their employer is unwilling or unable to hire enough new staff that current employees would not feel overworked. Training facilitator James went as far as to say that his company’s claims about staffing levels were “nonsense”, and their assertions that they don’t unduly pressure staff were untrue; “in practice they’ll be cracking the whip”.

“If you were interviewing a manager here they’d be telling you, ‘Oh no, no, no, we don’t put any time restraints on them, oh no, no, no, that’s not person-centred care.’ Okay then, so you’ve got two members of staff looking after 24 residents and they’re off for 40 minutes [with a resident] … where’s the cover?”—James

Participants in our study reported numerous consequences associated with this kind of understaffing, from having to deal with too many residents per staff member to not having time to take breaks or drink and eat on shift. Susan, who manages an elderly care home, recalled how she was “literally running” between residents.

One care worker told us that in some cases residents had strict staffing requirements, as prescribed by their ‘care package’. This meant that the care company was prohibited from reducing staff ratios for these residents.

“The staffing… had to stay the same because of the complex people that we look after. So, their packages ensured they were given so many hours one to one, and they couldn’t take staff away if you get what I mean.”—Isabelle

Where it was not possible to reduce staff to resident ratios, employers often seemed to rely on the willingness of the full-time staff to pick up extra shifts. Laura felt this was in place of hiring more full-time staff or using expensive agency and bank staff.

Another key impact of understaffing mentioned throughout the interviews was that staff were having to take on extra jobs around the home (e.g., additional care responsibilities and paperwork, housekeeping and maintenance). One participant explained that the housekeeping staff in the care home (who were often ex-care-workers) were sometimes roped into doing care work when they were very short-staffed.

“They just tell the cleaner, ‘right, you’re caring for the day’… they seem to think it’s acceptable and they do it on a regular basis.”—Michael

Senior carers and deputy managers also reported picking up additional caring duties to support carers when the home was understaffed. For example, Lisa (deputy manager at a home for adults with learning disabilities), explained that because of staffing shortages she was doing “support work at night and management work during the day”. Rebecca told a similar story of having to work on the floor as a care assistant after finishing her medication round because the care company had failed to hire enough appropriately experienced staff for the job.

Beyond expanded care duties, Emily clearly detailed the extent of the extra workload some care workers were having to manage on top of their care duties (similar stories were repeated by several other participants).

“They took away our maintenance man… And we’ve got to do maintenance checks now. We have to do water temperature checks… legionella checks, the bath hoist… the hospital bed that we’ve got. I have to do maintenance checks on the minibus, I’m not even a mechanic… The smoke alarm, we’ve got to go around checking all them… All of them is extra paperwork that we’ve got to do as well… It’s just saving them money, isn’t it?… We’re still trying to give the same amount of care and the same level of care, but we’ve got all these extra[s] in our job role, even though my official title is mental health support worker, it should [be] maintenance worker, activities worker as well, cook as well, you know.”—Emily

4.1.3 Staff protecting residents

Instances of workplace hostility were raised by nine of our study participants. These ranged from rudeness and a lack of empathy, to shouting and swearing at staff members. Respondents also reported management giving staff the impression that they are replaceable, or even actively trying to force them out of their job role, in an attempt to discourage complaints. This perception of general hostility from management and/or the company was compounded by a fear from staff of being blamed for low quality care or for safeguarding issues.

“You don’t see these people and then all of a sudden they will swan in and they’ll point fingers at ‘Well you’re not doing this right and you’re not doing that right’.”—James

“We have safeguarding situations now a lot and again in this I am afraid because one time I could be blamed that I did something wrong and so… very often I am staying after my shifts, for example, 3-4 hours to fill in all documentation properly because I know if [the] documentation [is] not done I could be blamed.”—Rebecca

In the context of these challenging working conditions, participants reported that staff (and sometimes local care home managers) were acting to protect residents from the negative impacts of understaffing and service cuts. They expressed in different ways that the residents were their main concern, and that they would do what they felt was right, even if it was to their own detriment.

“First and foremost, the client comes before anything, it comes before anything else to do.”—Michael

This manifested in a number of ways, with some participants saying that they would rather any extra budget go towards food for residents, instead of staff perks or pay, whilst others put themselves at risk of being disciplined in order to provide the support they felt was needed by the residents. Others still spoke about how they tried not to allow under-resourcing and hostility from management to impact on the quality of the care they were delivering.

“It was only down to the staff themselves that the residents [didn’t] feel the impact more.”—Susan

And some participants even gave examples of staff reaching into their own pockets to make up for service shortfalls; for example, by bringing in food or toiletries for residents, or making financial contributions.

“I know they get so [and so] much allocated from the company, but what we do, it like tops it up a bit, so like we can afford to get them, like, Christmas presents and stuff.”—Emily

Two of our participants articulated that the willingness of staff to put the wellbeing of residents first was being knowingly exploited by their employers.

“That’s what I think [the company] use so much of… the caring factor of the individual [care worker] who cares for those [residents], and it’s almost like an unspoken ransom, you know, ‘Well if you leave what’s going to happen to [the residents]?’”—Lisa

From this quote, it seems that Lisa believes that her employer knows full-well what they are doing, and is taking advantage of the fact that workers care about the residents and would rather be exhausted and overworked than see anything bad happen to them. This commitment to residents is perversely acting as a source of value for employers, potentially enabling them to enact deeper cuts to servicers than they otherwise would, without immediately and adversely affecting quality of care.

“I’m one of them that always helps with staffing, because we don’t have staff. I don’t have to do it. But I said, I’m that type, when they ring, I feel bad to say ‘no’.”—Sarah

The impacts of a hostile work environment and of chronic under-resourcing and understaffing were felt keenly, with several participants reporting that staff were becoming ill with stress and that staff morale more generally was suffering under the strenuous working conditions. It is in this context that some of our participants reflected on the lack of support for staff from their company, and explained that they had to look after one another instead.

“The staff morale just went. It’s just non-existent now. They’re basically turning up to work to make sure they get paid at the end of the month.”—Jennifer

4.2 Cutting corners on service delivery—“They had choices to make, budgets to respect”

We developed this theme by identifying instances in the transcripts where participants had spoken about issues with sub-par service delivery; in particular, where they felt that tight budgets had resulted in corners being cut. Across the interviews, budget constraints were reported to have impacted on staffing levels (Section 4.2.1), medical and sanitary supplies (Section 4.2.2), quality and quantity of food for residents (Section 4.2.3), timely maintenance of equipment and the built environment (Section 4.2.4), and access to enriching activities (Section 4.2.5). All of which participants felt was detrimental to the quality of care and service delivery they were able to provide to residents. All sixteen participants contributed to this theme.

4.2.1 Staff

When asked whether staffing shortages were impacting quality of care, a couple of our interviewed care home workers were adamant that the difficult working conditions didn’t affect the care they were delivering. However, this sentiment was far from universal, with many explaining that under-resourcing was preventing them from being able to spend as much time as they would like to with residents, or deliver the care they felt they should.

“We have to skip some stuff, because it’s just two people. Two people cannot do four people’s jobs.”—Sarah

Concerns over how this under-resourcing was impacting patient wellbeing and safety were also prevalent among interviewed staff. Jennifer, who worked as a senior carer in an elderly residential home, recalled how patients had to “sit wetting themselves” because of the lack of available staff within the care home. She also raised concerns that medication wasn’t being delivered in a timely way because the senior carer was having to deal with too many residents.

“All the medication is all hit and miss. There’s one senior doing all three floors so she’s probably giving out medication for at least 45 people. All the timings will be out.”—Jennifer

In the extreme, James explained his experience of delivering end of life care under poor staffing conditions:

“This is going to sicken you now so be warned—you’ve got to get to the stage that, irrespective of how responsive you’ve been to a resident who’s really failing and who’s coming up to the end of their life, only then right at the very end of this do you get a response, do [the company] put an extra member of staff on maybe for half a day, and you’re sitting there going, all this would have been prevented.”—James

4.2.2 Medical and sanitary supplies

Participants often reported that access to adequate medical and sanitary supplies and equipment was lacking. For example, Michael (a senior care assistant at an elderly care facility) explained how his employer “point blank” refused to buy an appropriately sized bed for the larger residents in the care home, while others spoke about restricted supplies of sanitary pads and personal protective equipment.

“Even pads, they would tell us ‘We are on a budget. You have to use one pad a day’.”—Sarah

In the eyes of our participants, such restrictions were detrimental to the quality of care they were able to provide to residents. Laura even felt that the rationing of surgical masks had caused higher rates of Covid-19 infections within her care home.

“We lost a lot of people over it, a lot of people we shouldn’t have lost.”—Laura

4.2.3 Food

Six of our study participants spoke about the poor-quality food that was being provided for residents. Michael lamented the fact that all the food the residents receive is cheap and mass-produced.

“There’s no nutritional benefit in it, it’s just crap. It’s that bad right, that staff will bring cakes and things in for tea.”—Michael

Meanwhile, Jennifer emphasised the knock-on effects this has on residents’ broader wellbeing.

“When you’re hungry you’re agitated, so if you get hungry people at night they’re not sleeping properly because they’re hungry.”—Jennifer

Senior learning assistant Amanda felt that these kinds of food budget restrictions were a result of the goal of the service “to be profitable”.

“That was the aim of the service quite clearly and because of that… they had choices to make, budgets to respect and that would have had an effect on everything in the running of the house.”—Amanda

James was particularly concerned that money was going to managers’ bonuses and “leakage” to offshore companies, rather than being spent on improving the food provided to residents.

“When you start to know all about the leakage, we could feed our residents much better, we could have more staff in there, not a problem.”—James

4.2.4 Equipment and maintenance

A number of our participants complained that their houses were run-down and felt that budgetary constraints were driving underspending on maintenance and equipment replacement in the care home.

“Now they’re saying they’ve run out of money, and we’re not allowed any repairs unless it’s an emergency until April.”—Emily

Amanda spoke about the long wait times to get things fixed, comparing these problems starkly to the approach of the previous owner who did weekly maintenance checks around the home and fixed problems quickly. David also spoke about proactivity with regards to maintenance as an important part of ‘good’ ownership.

“The amount of times that we said we need things fixing… the tumble dryer’s broken, needs fixing, [the] washing machine needs fixing, the dishwasher needs fixing. You know, household things that are important on a daily basis… I personally raised a problem that has been there since I started working in 2015, that was the dishwasher. Simple things that you would think all it takes is one person to go and buy a new one and fit it in, simple as. Five years down the line, still a dishwasher that doesn’t work.”—Amanda

Throughout the interviews, a particular framing of these budgetary issues cropped up a number of times. Participants explicitly contrasted the size of the salaries and profits that people in the upper management/ownership of the company were taking home with the degree of under-resourcing of things that were deemed fundamental to service delivery. Care home manager Isabelle captured it well:

“I was disgusted, if you like, because the care home is in a pretty poor state of repair, and it’s really evident. If you were a guest here today, you would think oh my life, how are these people living and working in these conditions. So, when [the new company] came with all… their flash cars and their nice clothes and their big houses and fancy holidays… I mean I’ve got doors here that blow open, French doors that blow open in the strong winds, because they’re just not fit for purpose. It’s shocking that, you know, they live that lifestyle, yet the service users don’t have a nice home and that really upsets me.”—Isabelle

4.2.5 Activities

Finally, a number of participants bought up a lack of access to enriching activities. Each of them felt these missing activities were important for residents’ overall wellbeing, with Robert and Lisa both highlighting how the small “almost intangible things” (Lisa) can make a difference. Speaking about the service under the old ownership, Robert felt that they did more activities with the residents, and that they would “go out and actually make an effort to, you know, have a nice day”. Meanwhile, Michael had a particularly jaded view of the implications of missing out on a broader approach to care, comparing his care home to a “prison for pensioners”.

“It’s just basically containment and just wait for you to die and we’ll get somebody else to fill your room.”—Michael

4.3 Covering up mismanagement—“I think [they] have no idea how to run a care home”

This theme captures participants’ feelings that their employer was mismanaging their care home (Section 4.3.1), and that they were more interested in how the care home looked to families and the regulator than they were in the quality of the care being delivered (Section 4.3.2). Given the self-selecting nature of our study it is unsurprising that many of the people who came forward to take part in our interviews felt that their employers were not offering the kind of care or working conditions they would like to see. Indeed, many of the interviewed staff felt that their employers were making poor decisions about how to run their care home.

“I think [the company] have no idea how to run a care home… I think anywhere that has that [company] motif, I don’t think it’s right good.”—Jennifer

Examples of employer-incompetence recalled by our participants included: hiring staff and managers who were inexperienced or unqualified; pressuring staff to take on residents who were not suitable for their particular care home (e.g., due to extra medical needs); and implementing inappropriate policies and procedures for their type of care home (e.g., an unnecessary activity-based checklist for adults in supported living who have full capacity). We discuss several of these examples in detail below, focusing in particular on incidents where mismanagement was framed by participants as being deliberate and motivated by the financial aspirations of the employer.

These issues were also communicated by those working in small, privately owned companies, with more of an emphasis on the owner behaving in a hap hazard or renegade fashion: “He was a bit of a wheeler dealer” (Isabelle). However, in these cases, both participants were managers and both reported being more able to retain control of the day-to-day running of the business than those participants from larger, investment-firm-owned care chains.

“He had no say in the day to day running of anything because he didn’t really know what he was talking about. So, I wouldn’t have had that respect for him if he had even tried.”—Isabelle

4.3.1 Care home mismanagement

First, several participants raised the fact that their employer was hiring inexperienced or poor-quality staff. Michael spoke about his frustration that his employer would bring in agency staff who “don’t know the lay of the land” and who, as a result, were making a substantial number of medication errors. Exasperation at poor staffing policies were echoed by other participants. Rebecca, for example, who is also an elderly care senior care assistant, commented that it seemed her employer thought they could just hire anybody and “everything will be okay”. She immediately reflected: “it’s not like that”.

“It’s very stressful, plus agency staff they are not confident with our company’s documentation and some of them [are] refusing to fill it [in], which means I need to it.”—Rebecca

These could be straightforward examples of poor hiring decisions by care providers, potentially reflecting the difficult recruitment environment in the UK care sector[7]. However, they might also be examples of employers intentionally hiring cheaper labour, without due concern for the consequences on permanent staff and residents. In the case of agency staff, they can in theory work out cheaper in the long run than hiring additional members of full-time staff, if they are used sparingly to fill staffing gaps. This is because, although their hourly rate is higher than full-time staff, the employer doesn’t have to cover expensive annual overhead costs.

Concerns about poor hiring decisions also extended to management positions. Several interviewees offered examples of a new employer putting in place management who were unqualified and who lacked the required knowledge about how to do their job effectively. When talking about a manager who was unable to explain basic hygiene regulations, James quipped: “£98,000 a year? You must be mad”. Similarly, when speculating on the reasons behind hiring a manager with “no qualifications”, Jennifer, who worked as a senior carer in an elderly residential home, felt that there were ulterior motives at play, with the employer trying to cultivate a certain reputation for the care home.

“I think they’ve just got her in to make it look good.”—Jennifer

A second example of perceived mismanagement was the general disregard from some employers for the nuances of choosing which types of residents to take on. Some participants reported pressures from above to take all and any service users, even if they were a poor fit with other service users already living in the home, or if their needs were too great given the available resources. Support worker Robert, who works with adults with learning disabilities, recalled how his care home had taken on a service user who “didn’t mix in with the other service users too well”, and that the upper management were “pushing to just fill this bedroom”. Others also framed the lack of attention to resident dynamics as being motivated by a desire to fill beds and maintain high occupancy levels.

“If we could not fulfil that man’s requirements then that man should’ve went to some place that did and that’s a nursing home; you’d have extra staff, you’d have everything else. We couldn’t fulfil his requirements. We didn’t fulfil his requirements for months… That’s down to management then to turn round… forget about the bum on the bed, because that’s what it was. This is my estimation. So much more could’ve been done for that man.”—James

Third, a number of our participants had experienced owners who were new to their sector. For example, Will—a support worker for adults with learning disabilities—spoke about how his care home was the first learning disability service that his charity had run, and how the owners were investing large amounts of money into trying to ensure that it didn’t fail.

“They are absolute[ly] adamant they need this to work because it’s their flagship, otherwise we would have got handed back [to the local authority].”—Will

For Isabelle, the inexperienced owner meant that her residential care service had been given blanket policies and procedures that “were really for domiciliary care and supported living”. She spoke about how she wished she had an owner who “knew about the care field”, who took “an interest in the service users” and who helped “to progress the service”. These comments portrayed an image of an employer who had little interest in the care being provided in the home. Similarly, Emily saw her mental health service “voted down by CQC” (Care Quality Commission) as a result of the incorrect paperwork that was put in place by the new owner. Both participants felt frustrated that their employers’ involvement in the sector seemed to be largely financially motivated, with little interest in staff and residents.

“The staff morale dipped big time because we were perplexed as to why this company has taken us over and they have no, well very little understanding of mental health. So, they saw these figures and thought ‘oh we can make some money there’ and they bought our company. So, it was, like, okay thanks.”—Emily

A final aspect of mismanagement raised by participants during the interviews was the general lack of vision for the future of their care home from their employer. Using the example of the digital development of the company, David, who works with adults with learning disabilities, compared the more proactive “adapt and sustain” approach of his care home’s new owners to the approach of the old owners, who he described as taking the attitude “Okay, whatever comes let it come”, with no long-term plan for adaptation and development. Frustration at the lack of long-term planning at the level of the individual care home was mirrored by others.

“If you leave a complete floor that does require refurbishing, equipment put in place, etc, etc, and it’s been lying there, dormant, let’s say for the last five months, six months, doesn’t that make it worrying?… For me that doesn’t give an indication of having any sense of direction or how you’re going to take the home forward.”—James

4.3.2 Covering up the problems

Many participants spoke about a preoccupation with hitting KPIs and targets and making the care home look good to families and the CQC, rather than delivering the best possible care to residents. A number of participants told us about how their employer was asking them to prioritise paperwork over care delivery and, in one case, to even falsify paperwork to make it look like the care home was delivering better care than it actually was. While some acknowledged the importance of paperwork from a safeguarding and accountability perspective, many still felt that it wasn’t portraying a true picture of what was going on in the care home.

“It’s… not correlating to how we actually are.”—Laura

Because this extra paperwork was often not coupled with additional resourcing to give care workers the time to do it, some of our interviewees argued that it added to the pressures of the job and even took time away from being able to do the care-focused parts of their job.

“It’s the swan theory, isn’t it, you know, we’re gliding along the water, but our feet are going like the clappers underneath because that’s the truth of it. You know, yes, we’re under pressure with everything else, we will try and provide the paperwork to meet the goals, to meet the quality, to meet the financial audits, etc, but we’re just frantically swimming like hell underneath to do it all.”—Lisa

Indeed, several of the interviewed care home workers felt that the focus on paperwork was more about covering the backs of staff and management if anything goes wrong, rather than being about ensuring quality. Sarah, who is a care assistant at a residential home, even recalled being asked by the care home manager to lie on her paperwork, to say that she had turned a resident in their bed (to avoid pressure sores) every two hours, even if she hadn’t.

“When I say, ‘Why?’ They say, ‘It covers our back’. That’s what they say. And I just drop my pen, I say, ‘I’m not writing it. I didn’t do it.’”—Sarah

Participants also spoke about other strategies aimed at putting on a show for the Care Quality Commission whenever they inspected the home. These strategies ranged from adding extra agency staff on shift to “make it look busy” (Michael), to removing staff members “who are very outspoken” (Sarah) from the rota when the CQC inspectors were due. These stories were often immediately contrasted with a reflection on how the care home went back to normal staffing levels straight after the inspection.

“When I was in the other day, we were that understaffed the manager was having to mop the floor.”—Thomas

By coercing staff into covering up the aspects of care provision that are falling short of the expected standard, Sarah felt that the situation was being enabled to continue.

“My home manager said, ‘Oh, we passed the CQC, that was a surprise.’ So, I was [also] surprised, because there were things that were still wrong. They were still wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong.”—Sarah

4.4 Failing to communicate—“I don’t trust them, and I don’t think they’re being honest”

This theme describes the disconnect between those living and working in the care homes, and the upper management of the company, characterised by poor communication (Section 4.4.1) and a lack of transparency from participants’ employers (Section 4.4.2). This includes participants’ accounts of difficulties in communicating feedback to the company and affecting change within their workplace, as well as their impressions that the company is disinterested in the care home, with some reflecting on how infrequently upper management would set foot in the home. All told, the lack of effective channels through which staff could communicate their needs and issues left participants feeling ignored and disempowered.

“We felt that we were completely left out, ignored.”—Amanda

This, combined with a lack of transparency, led some of the interviewed care home staff to distrust their employers: “I don’t trust them, and I don’t think they’re being honest” (Isabelle); with Lisa likening her employer to the suspicious company at the centre of a murder mystery TV series: “people know things; things have happened that nobody talks about”.

4.4.1 Poor communication

Many study participants reported a general sense of distance (either physical or metaphorical) between the upper management and the staff and residents in the care homes. Some spoke about their perception that the company was completely uninterested in what was going on in the care home.

“I had no personal relationship with like the upper management. They never really came in to talk to the staff… There wasn’t even like meeting with the upper management. They were just up in the office all the time. Like they never came onto the floor… if ever.”—Robert

A number of others emphasised the very physical process of isolation, with their unit manager becoming progressively more closed-off after the new ownership took over.

“Within that time, in service as line manager, they have gradually become more and more detached from staff as if in less around the house, more closed into their office, door closed, in constant meetings, constantly busy.”—Amanda

In an extreme case, Rebecca said that her new manager remained hidden away in the administration building, telling us that “for three months some of us had no idea how she looked”. Care home managers occupy a unique position within the social network of care home companies, operating as gatekeepers that can either facilitate or hinder the flow of communication between care staff and upper management. As such, the physical process of isolation described by Rebecca and others may well have an impact on the perceived workplace autonomy and wellbeing of staff.

“Disjointed, isn’t it? … the chain of command from the top right to the care staff… that link should be strong, the communication should flow both ways. For the carer staff it’s always one way traffic.”—James

In addition to the sense of distance felt by some participants between themselves and upper management, many of the care workers we spoke to described more generally the limited (and sometimes non-existent) avenues for affecting change within their home. Some recalled their attempts to communicate with management and HR about ongoing issues, saying that they received no real response or action from the company.

“We exhausted every avenue that myself and my Deputy humanly could to get them to understand this wasn’t working, it wasn’t safe and it wasn’t right, you know.”—Susan

Jennifer talked to us about ongoing issues with racism in the care sector, and in her care home in particular, emphasising that the sector did not cater to the haircare, skincare, or food and language needs of people of colour. She tried to secure some training for the staff on these issues but reached a dead end after speaking to her manager.

“She did say she’d look into it, [but] nothing ever came of it because you’re not supposed to have ideas, you’re supposed to just be brain-dead.”—Jennifer

Others echoed similar frustrations around a lack of responsiveness to feedback.

“When we complained that we didn’t have the right equipment, safety equipment for around Covid time, nothing happened… It felt like I was shouting into a void because it may change for like a day or so but it always went back to where it was.”—Laura

Some participants bought up what appeared to be tokenistic offers to give feedback on their care home. For example, Rebecca recalled a time when she had tried to raise an issue with the care home manager. She contrasted the friendly welcoming tone of the email response she initially received, seemingly inviting open communication—“If you have any questions or you want any more information you can come and see me”—to the overtly hostile reaction she encountered when actually following up in person: “they blamed on me and they shouted at me, they shouted in very rude ways”. Other companies sent out anonymous questionnaires to their employees. However, Amanda noted that the issues she raised through the feedback forms were “never addressed”.

“We were saying we actually need things for the young adults, we need things for the people we support… We felt like we were never seeing any of the executive[s] coming into our settings… No one was ever coming to check what was needed fixing.”—Amanda

This left some wondering “what’s the point in saying anything because nothing happens, nothing gets done” (Lisa). As we raised in Section 4.3 above, Sarah—as an outspoken advocate for improving care home conditions—was removed from the rota when the CQC was due for its inspection, further impairing her ability to notify anyone about the poor working conditions.

As a result of the limited channels for communication, there was a ready recognition among many of the participants that they were very far from the decision-making centre of the company, with little to no means to effect change within their workplace.

“I can phone them but it’s very rare you would ever have a meeting with them face to face. Because you’re at the bottom of the food chain, you’re the cogs of the wheel but they’re the seat and the handlebars, do you know what I mean?”—Michael

By closing the channels for formal communication, these care companies are inhibiting workers’ ability to resist exploitation or demand change.

“If I want to talk at the AGM, I have to buy a share in order to be able to say, ‘you’re shit’.”—Thomas

4.4.2 Lack of transparency

Finally, a lack of transparency—sometimes combined with empty promises to staff that their ‘lot’ and the ‘lot’ of residents would improve—came up a number of times as a cause for concern for our interviewees. The transparency concerns ranged from the opaque structure of the company as a whole, with complex corporate group structures that “end up all back, as it is, in Guernsey” (James), to behind-the-scenes changes to staffing contracts. Lisa realised that her employer had been keeping things from the staff when she moved into a management position within her care home.

“We’re subtly having our hours reduced without actually being advised that, you know, ‘Because of restructuring, because of how we are going to run this business, this is what is going to happen, are you happy or unhappy with that?’ You know?—Lisa

Concerns over a lack of transparency were echoed by other participants, most of whom were in management positions. Many of the same participants also expressed frustrations about how upper management would promise “all this, that and the other” (Emily), claiming that they were going to improve conditions within the care home (e.g., new buildings, equipment, etc), but failing to deliver on those promises. James felt that the rhetoric was just empty bluster.

“All you’re doing is you’re standing there trying to blow smoke up [our] arses.”—James

4.5 Prioritising profit over care—“It was all money, money, money”

This fifth thematic cluster reflects the fact that many of our participants felt their employer was much more interested in making money than in the wellbeing of their staff and residents. Some participants spoke indirectly about how their new employer felt very corporate (Section 4.5.1) and/or took little interest in the care home staff and its residents (Section 4.5.2), whilst others were more direct in their assertions that the company was there to make money (Section 4.5.3). The theme ties a lot of the issues from previous themes together, with participants offering the company’s financial aspirations as an explanation for various issues, including understaffing and cutting corners on service delivery.

4.5.1 Corporate style employer

Some participants spoke about how their new employer felt “more corporate” (Susan) whilst others described a top-heavy company structure characterised by large salaries and complex ownership structures. Participants who worked in charities also reported similar corporate-like structures.

“Charities may well be split into two… there will be the care and support element, and another element may well be housing.”—Charles

“I’m only surmising that the founders of these charities are definitely on a lot more money than I am.”—Will

In addition, two participants recalled the use of corporate-style employee incentive schemes, such as flu and Covid-19 vaccination bonuses and “refer a friend” programmes (Emily). The clearest example was a “system of perks”, introduced at Amanda’s care home, that was linked to a weekly feedback questionnaire. Not only did Amanda report that care staff would rather the money for perks be spent on better quality food for residents—“we believe that that is more important than our perk box and all that crap”—but she also highlighted that the perks often didn’t really apply to care staff and were more targeted at people with manager-level salaries. For example, there was a car discount that “was only applying to certain types of cars that were completely out of our budget as care workers”. More fundamentally, she captured the mismatch between these corporate-style incentive schemes and the reality of day-to-day work in a care home:

“You know, a perk box, benefits and all that, is all really nice and it sounds really nice; in reality, it doesn’t really work. It’s not our job, it’s not what we’re doing. We’re looking after people, you know, we’re feeding them, we’re washing them, we’re bathing them, we take them out in the community… This is what we do on a daily basis at Christmas time, Easter time and it’s, we’re not there to fill in a questionnaire online at the end of the week.”—Amanda

4.5.2 The company doesn’t care

Participants also expressed in many ways that they didn’t feel their companies cared about residents or staff.

“Don’t say they all care, it’s all about money and numbers, right, that’s it, that’s it.”—Will

This seemed to extend particularly to the health and wellbeing needs of staff. For example, Thomas spoke to the new company about his disability when they first took over and was told that they had good systems in place to support him, but he never heard anything more from them.

“I feel as a disabled person that the company as a whole don’t give a hoot.”—Thomas

Emily also detailed how the company reacted to her medical needs, saying:

“I was off for four months from Easter, and only the manager actually phoned, that’s because I get on so well with him… but area manager, anyone else from HR or anything, not one message, not one email, nothing. We just feel like we’re just a number basically.”—Emily

She added:

“I am medically exempt from wearing a face mask, but [the company] have stipulated… to the manager that I have to wear a face mask at all times, and if I don’t, I’ll be sent home and I’ll get sick pay for four months and then probably dismissed.”—Emily

This aligns with the accounts of hostility that we summarised in Section 4.1.3, reporting on the exploitation of care staff.

4.5.3 Only interested in money

Most strikingly, many of our study participants spoke directly about how they felt their company prioritised profits over care. Eleven of the interviewed staff said something to the effect of ‘it’s a business’ or ‘it’s all about money’ at some point during the course of the interview.

“I think the reason people come and do this, buy this, and own this is simply to make a profit.”—Isabelle

“It is more about money than the people, definitely.”—Emily

“It’s all about business. It’s all about their profits.”—Sarah

Michael felt that the expectation of a “return on your money” by investors was linked to a workforce strategy of “squeeze and squeeze and squeeze”. This acute awareness by some participants of the role of money and profit in motivating the involvement of their employer in the sector led some to argue that a not-for-profit model of care would be better for residents and workers. However, this would need to be accompanied with broader changes to the structure of the sector because, as Will commented, even his charity employer was in it “to make money” for certain people (e.g., high salaried bosses). Others said that they did feel comfortable with the for-profit element of care delivery to some extent, as long as it wasn’t excessive.

“So with every £100 coming here, there’s £13.95 never gets here and it’s never on the books, it’s never taxed, it’s never nothing… Excuse me because I get really annoyed with these things… See, I understand about capitalism, I mean, okay, you’ve got investors and stuff, that’s fair, they want to make money, that’s fair, however such leakage is disgusting.”—James

When asked about the future of adult social care, many highlighted the potential advantages of taking profit and other large corporate structures such as large directors’ salaries out of the care sector, with some arguing for an National Health Service (NHS) style model, while others preferred the idea of smaller independent charities or cooperative care companies. Participants felt that these models of care would offer a variety of benefits: more transparency, accountability, consistency in what was being offered across the country, better upkeep of buildings, and more staff recognition and fair pay grades. Susan felt that, however desirable, moving towards an NHS-style model was not a realistic goal and felt that we do not have the money, time or power to make the necessary changes.

5 Findings: Review of accounts

In this section we review the accounts of fifteen of the UK’s largest adult social care groups. Our sample consists of six for-profit groups that have an investment firm owner/significant partner, five for-profit groups that are not owned by an investment firm, and four not-for-profit groups. We look at accounts for the years ending 2015, 2018, and 2020. Overall, in 2020 most groups were reasonably profitable with an average of 23% of their turnover remaining as operating profits (i.e., a 23% margin) which was slightly higher than in 2018 (22%) and 2015 (21%) (see Table 2 in Section 3 above). By operating profits, we mean earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, amortization, and restructuring or rent costs (EBITDAR), excluding exceptional items. This average excludes the five groups where we were not able to calculate their EBITDAR in 2020.[8] Avery Healthcare had the highest operating profit margin across all years, which partly reflects the fact that it has an above-average proportion of self-funded residents who typically pay higher fees.

5.1 Employee remuneration

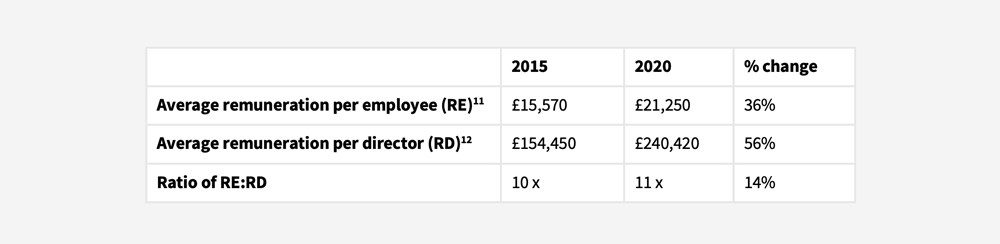

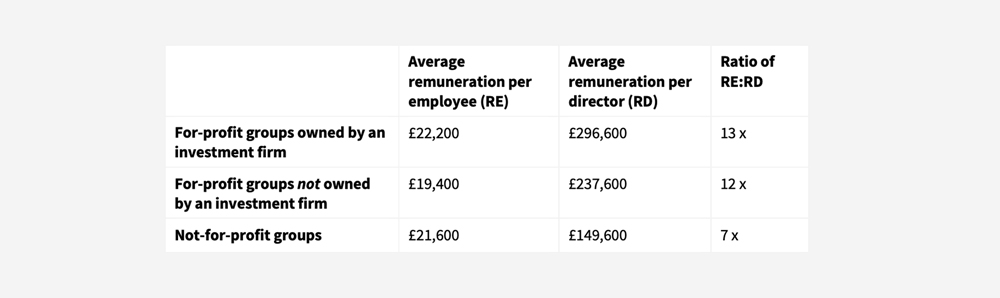

We calculated average remuneration (i.e., pay including basic salary and any additional payments such as overtime, bonuses, social security costs and pensions) per employee and per director for our sample.[9] Across our sample we found that, from 2015 to 2020, average remuneration per director had grown at almost double the rate of remuneration per employee. This means that by 2020, the average director’s remuneration was 11 times higher than that of the average employee. See Table 3 below.

Table 3 | Change in average remuneration per employee or director from 2015 to 2020 (sample of eleven care groups with comparable data). These figures are an average across all ownership types[10]

Our findings for average remuneration per employee are similar to those reported by Skills for Care’s adult social care workforce estimates, with yearly pay for a care worker at £20,700 and for a senior care work at £25,700 in 2020/21 (Fenton et al., 2021, p. 95). The differences will be in part because we are only looking at a sample of care companies, not the whole sector, and also because our estimate of remuneration per employee reflects the full cost to the employer, and so includes pension contributions and social security costs. We also calculate pay for all employees in a company below director level and so include higher paid managers and administration staff in the figure too. Additionally, most accounts provided us with average numbers of staff in a year, whilst Skills for Care uses FTE (full time equivalent) annual pay.

When comparing across groups, for-profit care groups owned by an investment firm paid their directors on average more than other for-profit groups as well as not-for-profits, with average remuneration per director (in 2020) at £296,600 for investment firm-owned groups, versus £237,600 for other for-profits that are not owned by an investment firm, and £149,600 in not-for-profits (see Table 4 below).

Table 4 | Average remuneration per employee and director in 2020 (sample of eleven care groups with comparable data)

The ratio of average remuneration per director to remuneration per employee has grown substantially between 2015 and 2020 for investment firm-owned groups, whilst it has dropped slightly for not-for-profit groups (see Figure 1). It fell in not-for-profits because remuneration per director grew by only 3% whilst remuneration per employee grew in line with the average at 37%. By 2020 investment-firm-owned groups had a higher remuneration ratio (13 times) than other for-profit or not-for-profit groups. This is because the average director pay was higher in investment firm-owned groups. The discrepancy between the average director’s pay in investment-firm-owned groups and the average in not-for-profit groups was equivalent to the average salary of more than six employees.

Figure 1 | Ratio of average pay per director to pay per employee in 2015 and 2020 (sample of eleven care groups with comparable data)

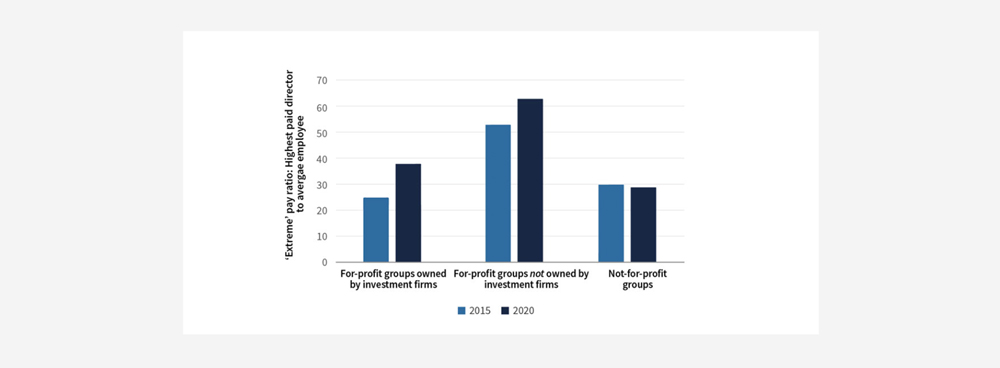

In terms of the ratio of highest-paid director to average employee remuneration, the for-profit groups not owned by investment firms (three out of five reporting) had the highest ratios, with the highest paid director being paid, on average, 63 times more than the average employee in 2020 (see Figure 2). However, this is driven by one company in particular, Runwood Homes, who had a ratio of 165:1 in 2020. The one not-for-profit company that reported its figures had a similar ratio to the investment-firm-owned groups (4 out of 6 reporting) at 29:1 and 38:1 respectively in 2020. This pay disparity grew between 2015 and 2020 for all for-profit groups (including those owned by an investment firm, and those not). It is also worth noting that the yearly pay of a company director in an investment-firm-owned group is likely to be an underestimate in the long-run because they typically receive a large chunk of their compensation upon the successful sale of the business.

These ratios of highest paid director to average employee remuneration are broadly in line with ratios in other large companies. For example, a report from the High Pay Centre in 2020 found that the average CEO to median employee pay ratio for FTSE 350 companies was 53:1 (Kay and Hildyard, 2020). However, they stand in stark contrast to the much smaller pay disparities in the NHS, where the remuneration of the chief executive of the NHS is approximately seven times that of the average employee (authors’ own calculation based on data from Cabinet Office (2021) and NHS Digital (2022)).

Figure 2 | Average ratio of highest paid directors’ pay to pay per employee in 2015 and 2020 (sample of eight groups)

5.2 Key performance indicators

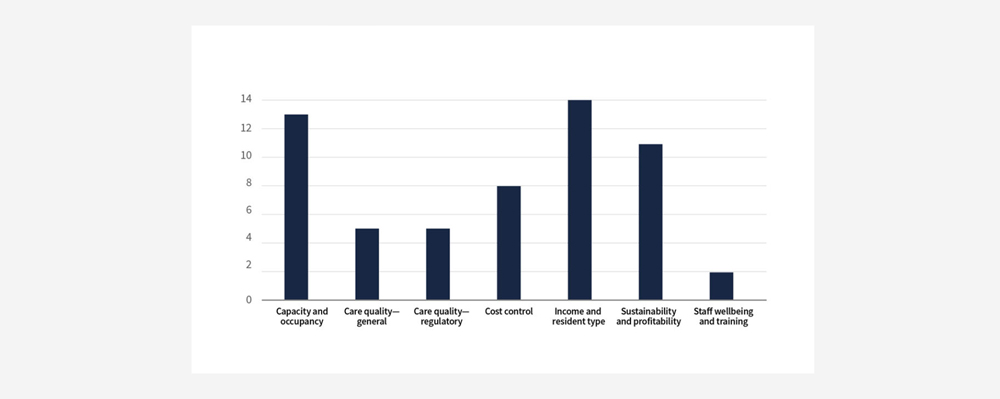

Reviewing all fifteen companies we found that the majority had KPIs in the ‘capacity and occupancy’, ‘income and resident type’, ‘sustainability and profitability’, and ‘cost control’ categories (see Figure 3 below). This reflects the fact that the key profitability drivers in the care industry are occupancy, income, and limiting the impact of cost increases. Indicators monitoring staff wellbeing and training were less commonly included, despite staff being the main input for a care business. Those that did revolve around staff were usually focused on labour cost per bed, hour, or resident; i.e., considering staff as a form of cost to be managed rather than an asset to be nurtured. This attitude was particularly visible during the pandemic when it was reported that some care staff were not receiving sick pay when self-isolating, forcing them to use up their annual leave or risk returning to work early in order to financially sustain themselves (UNISON 2021).

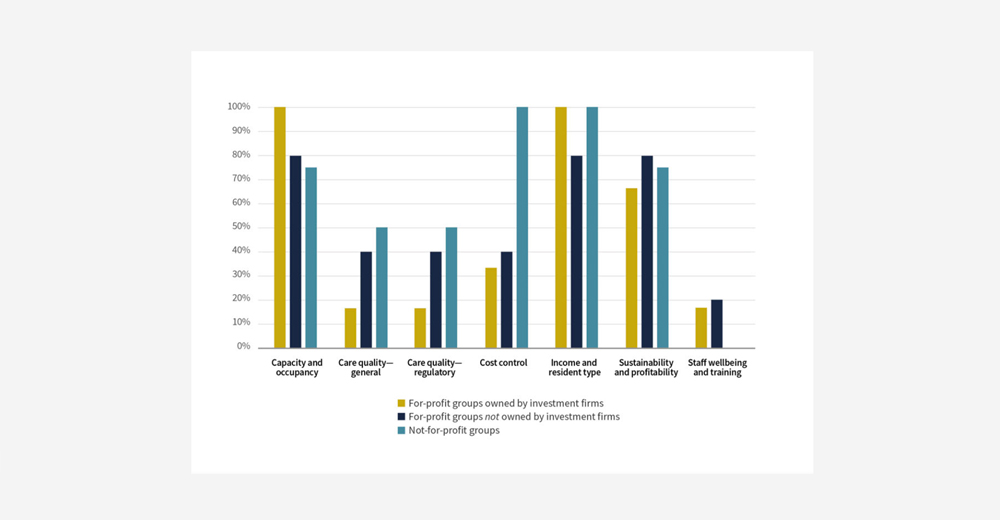

We broke the KPIs down into different ownership groups, finding that investment-firm-owned groups were most likely to have KPIs in the categories of ‘capacity and occupancy’ and ‘income and resident type’ (see Figure 4 below). Within the category of ‘income and resident type’ there were notable differences in the KPIs used by investment-firm-owned groups and not-for-profit groups. The former were heavily focused on the proportion of self-funders and fee rates, whilst the latter focused more on revenue. Similarly, within the ‘sustainability and profitability’ category, there were differences between for- and not-for-profits. For-profit groups (both investment-firm-owned and others) were more focused on KPIs relating to operating profitability, and their ability to generate sufficient cash to pay their debts, whilst not-for-profits focused more heavily on financial sustainability and generating a surplus for reinvestment.

Figure 3 | Number of companies with at least one KPI in each category in 2020

Figure 4 | Proportion of care home groups with KPIs in each category by ownership type in 2020

We also found that not-for-profit groups were more likely to have KPIs relating to ‘cost control’. These were particularly focused on monitoring costs per unit, such as cost per resident per week, management costs per unit, and staffing cost per bed. It is difficult to say concretely, but there may be a number of reasons why not-for-profits consider cost control KPIs a key business metric to report on.

First, according to industry analysts LaingBuisson (2021), not-for-profit care groups tend to focus principally on residential homes whilst for-profit groups have a stronger focus on nursing homes. In 2018, they estimate that 73% of all not-for-profit beds are for residential care, whilst 53% of for-profit beds are residential (with the remainder being for nursing care). This is reflected in our sample, with 67% of the care homes in the not-for-profit chains in our sample registered as providing care without nursing (i.e., residential), whilst only 45% of for-profit care homes in our sample were offering non-nursing care (authors’ own calculations based on CQC data as at 1st March 2022). This may impact how easily not-for-profit groups are able to manage the emerging trend towards increasingly complex and costly residents in the residential part of the market.

Under budget pressures, local authorities have favoured providing homecare for elderly residents instead of paying for (usually more expensive) care home places, thus “generating savings” for the local authority (Laing Buisson, 2018, p. 54). As a result, over time, those residents who have been placed in care homes have tended to be those with more complex needs as “some of those who would previously have been placed in residential care are now receiving homecare services” (Laing Buisson, 2018, p. 53). This trend has been coupled with a preference by local authorities to place individuals in residential care homes—which generally have lower fees (LaingBuisson, 2021)—rather than in nursing homes. This has been described as a process of transferring demand “down the continuum of care services” (Laing Buisson, 2018, p. 53). Residential homes are typically less well-equipped to handle the needs and costs of higher acuity residents. This may explain in part why not-for-profits focus more explicitly on cost control KPIs, as a larger proportion of their business may have been impacted by this trend towards higher acuity residents.

The challenge of absorbing the higher costs associated with more complex residents may be even tougher for the not-for-profits groups in our sample for two reasons: one, residential homes have, on average, fewer beds per home than nursing homes (LaingBuisson, 2021), likely limiting their opportunities for economies of scale at the level of the individual care home, and their ability to spread the costs of new equipment and training across multiple residents. The average number of beds per home across the not-for-profit chains in our sample was 51, as compared to 61 beds in the for-profit portion of our sample.

Two, the not-for-profits (and for-profit groups not owned by investors) in our sample tended to be smaller in scale than the investment-firm-owned groups. This matters because it has been noted that larger groups can “exploit economies of scale” by, for example, taking advantage their “greater purchasing power for consumables such as utilities and food” (LaingBuisson, 2021, p. 15). The pressure to generate economies of scale to aid financial sustainability is notable across the sector. For example, the not-for-profit Anchor Trust stated before its proposed merger with Hanover Housing Association that a merger would: “drive down the cost of doing business, and follows several years of efficiency savings”, and that Anchor: “work[s] to mitigate the impact of cost inflation and uncertainty by a process of continuous improvement to drive down our cost base” (Anchor Trust, 2018, pp. 5, 9).